In her twenties, the New York poet Hilda Morley visited Hilda Doolittle, her namesake and mentor, in London. “Don’t publish too early,” H.D. advised her. How acutely Morley heeded her advice: she was sixty when her first collection, A Blessing Outside Us, was published in 1976 by Pourboire, a small press in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Shortly afterwards, Morley’s young publisher killed himself, and she found herself bereft of an early advocate but at the same time “stuck with distribution problems.” “Do you know any bookstores?” the poet asked friends.

That Morley’s exquisite poems could, nearly forty years later, still be seeking readers can only partly be explained by her friend Stanley Kunitz’s comment that she was “unaggressive about her work.” At her death in 1998, she had five published books; many more of her poems remain unpublished, awaiting excavation by literary expeditioners. Her colleague and admirer Denise Levertov remarked in her collection of essays Light Up the Cave (1981) that Morley had been keeping her poems up her sleeve. “When they see the light, it is in full ripeness. We fall silent before them.” men.” She quotes Olson as saying, “‘it’s nice, isn’t it, that we have the women we care about doing them for us—and it’s always been natural for them, too.’”

Big men with big ideas at Black Mountain were miles away, however, from the atmosphere among artist friends in Manhattan. In “The Eighth Street Club,” a chapter in her unpublished memoir of Wolpe, Morley recalls the joyous energy of the painters and musicians she and her husband socialized with in a loft on East Eighth Street—Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Edgard and Louise Varèse, Franz Kline, Ad Reinhardt, and Mercedes Matter (who founded the Studio School). Some of them she met through her second husband, Gene Morley, who had been a classmate of Pollock at the Art Students League.

In the same memoir, Morley compares Willem de Kooning’s idea of visual space with Wolpe’s similarly inventive idea of musical space. “The painters of the Club were opposed to the use of illusionist space, and the possibility of creating another kind of perspective… was of challenging urgency.” The European Wolpe and his worldly wife found an affirming home among the “explosive” talk of American artists, “in that atmosphere of loving elation, in that exhilaration, where it seemed that anything could be tried out.” The need for a “stockade” of like-minded artists was even more dramatic when rich collectors were received in unheated, cold-water studios in the Bowery.

For Morley the Abstract Expressionists’ solidarity was as necessary as that of the early Impressionists who gathered at Paris’s Café Guerbois. “Competition hadn’t set in. The art world belonged to the artists,” is how Elaine de Kooning described the era. And the master they emulated, according to Morley, was Cézanne, a painter obsessed with the problem of space and how to represent the conflict at the heart of nature, “the thrill of [nature’s] permanence along with the appearance of all her changes.” Her study of his importance for twentieth- century art has, says Morley, “never stopped and has brought me again and again to a clarification of what Stefan [Wolpe] achieved and what I aim for in my poems.”

While at Black Mountain in 1955, Morley found in the craggy hills of North Carolina the “light Cézanne was / thankful for continually.” In her poem “In Provence” she explores the painter’s devotion to natural light as well as his challenge to render that which is ever-changing:

In Morley’s universe, the “stars / Hilarious in their wheeling violence blow / air from our lungs, / blood from our bodies, / rock our bellies sick—.” The mountain “reaches for your face” and the “last leaves carry a message.” She crystalizes the energy of inanimate objects in this passage from “Still-Life,” based on late Cézanne watercolors:

Morley devours light as a painter devours light and—with Barbara Guest, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and others of the New York School—cast her lot with the artists whose work she loved and learned from. In “That Bright Grey Eye,” the eye is Turner’s at seventy-six:

What would that great colorist have done with a fiery late August sunset over the Hudson River, a spectacle Morley wishes Turner could have seen and “given back to us”:

The young girl in Vermeer’s famous portrait has a:

And in “Matisse: The Red Studio,” Morley recreates the process by which the painter’s arrangement of elements awakens the viewer’s “sight”:

Morley’s meditation on a landscape in “The Curve of the Water” unpacks the artist’s process:

In her preface to The Turning (1998), Morley credited the Abstract Expressionist painters with “saving my poetry from a retreat into the formal tendencies of past centuries.” Klee’s “innocent eye” corresponded to her “still small voice.” Picasso’s “tearings and upheavals” she could only grasp after she’d faced those elements in her own experience. But it was the New York artists who allowed her to find beauty in ugliness “without rejection.” “To transform or transmute these elements,” she wrote, “but still to embody them, was my task as poet.”

In this same statement of poetics, Morley explicitly compares the mind’s “darting, swooping movement,” its responses to its world, with the spacing of words on a page, “a movement full of stops, sudden coagulations and blockages, attempting to embody every turn of sensation or reflection in the way lines are broken to allow for ever-fresher emphases. A new kind of stillness can emerge from this use of space, for eye and ear at once, analogous, perhaps, to the stillness of a crowded interior by Matisse.”

So Morley records how painters helped her, not only to open herself to all forms of inner life, but to choose techniques that turn that inner life into words on the page. The “turning” of her title is a transformation of vision away from past to fresher forms of poetry. But it is emotional rebirth as well. After Wolpe died in 1972 of Parkinson’s disease, his widow struggled to live without him.

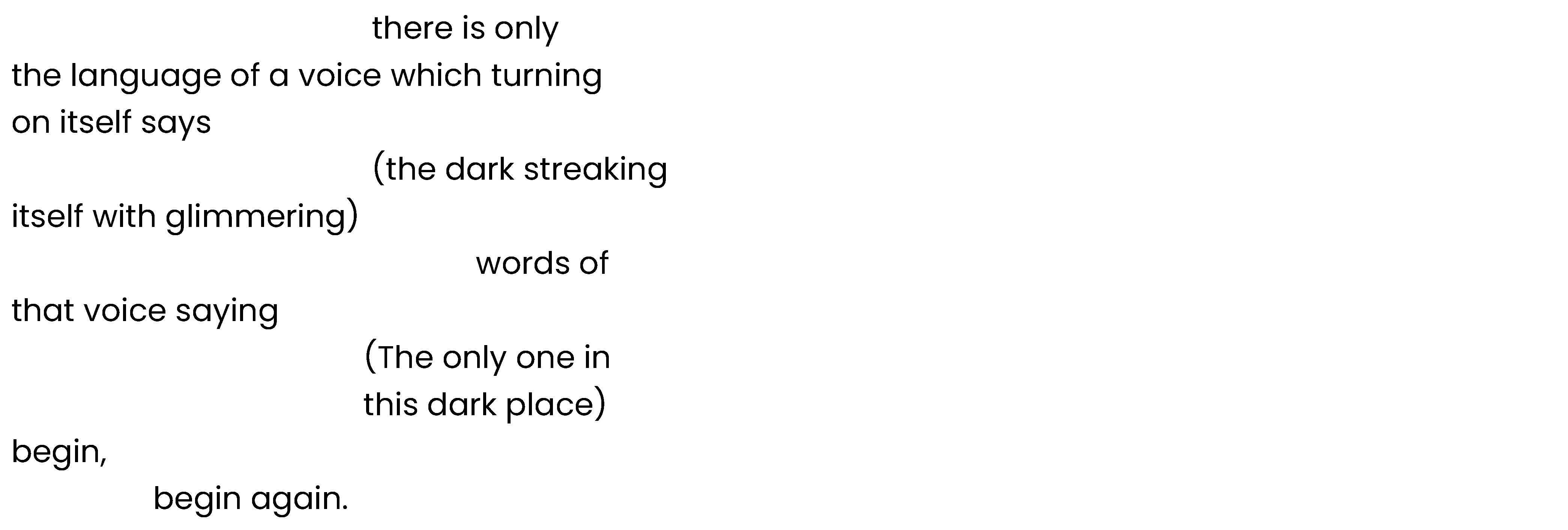

Her title poem “The Turning” (35) ends:

Stanley Kunitz claims in his preface to To Hold in My Hand (1984) that Wolpe’s death “liberated” Morley to focus on her own career, not her husband’s, to “set that power moving.” And, in fact, the poems she wrote after his death treat renewal and fulfillment more than loss and despair, and celebrate the will to start over. Morley embraces the joy of invention, “Where something is being made is / where joy is” (“The Last Rehearsal”). The first section of To Hold in My Hand is titled “Makers,” the last “Beginning Again.” Fittingly, for this book Morley received the Capricorn Award given to a poet over forty in belated recognition of excellence.

The irony to those of us lucky enough to know her work is that the poet Robert Creeley called “a milk maid,” and Duncan and Olson ignored, created “projective” poetry (exhibiting the notion that form is never more than an extension of content) far more accessible than theirs. As Levertov notes in her preface to What Are Winds and What Are Waters, Morley’s “poetry so truly (and intuitively, I think) manifests the real meaning of the often-abused concept of ‘composition by field’ Morley is one of the few who know exactly how to notate, or score, the words on the page so that emphasis, nuance, pace, all get into the reader’s ear.”

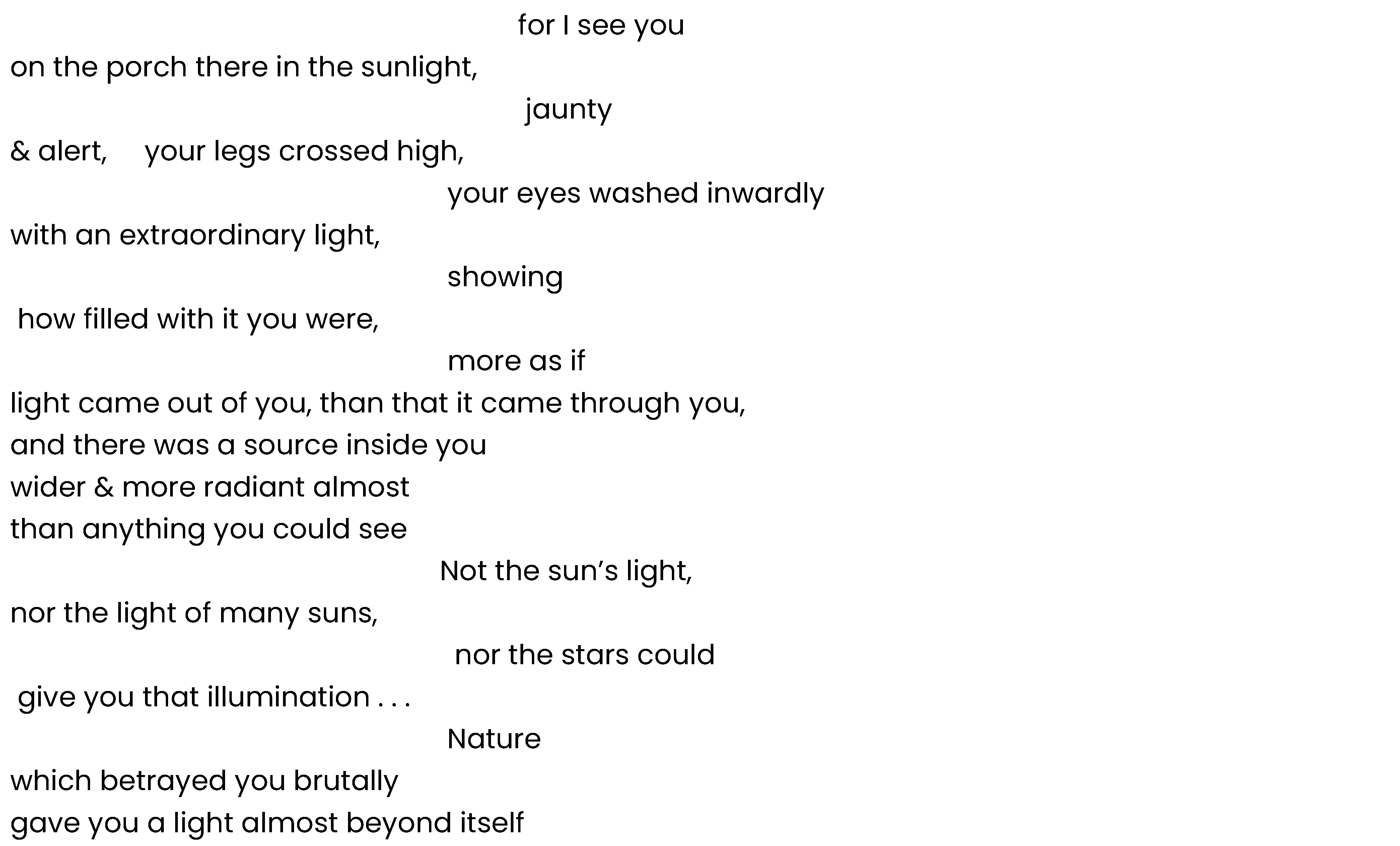

For Morley, the eye and ear are equal, says Carolyn Kizer in “The Light of Hilda Morley,” an essay in her 1993 book Proses; she achieves a balance between “music and meaning. Our pleasure as readers is physical, almost sensual,” and she cites these lines from What Are Winds and What Are Waters, a threnody for Wolpe:

That balance of music and meaning Kizer admires is reflected on the page: Morley breaks words to highlight them, placing them immediately after the previous word on a new line. There is nothing arbitrary about their alignment. The result is a paradox: nature gave Wolpe such moral radiance while it betrayed him brutally, a harmony of opposing elements. In a 1990 essay she published in Mid-American Review, Morley says the poet and musician both translate rhythms “stored in memory.” As a poet, she listens “to the sounds inside me, which are sometimes composed more of a rhythm than of specific words.”

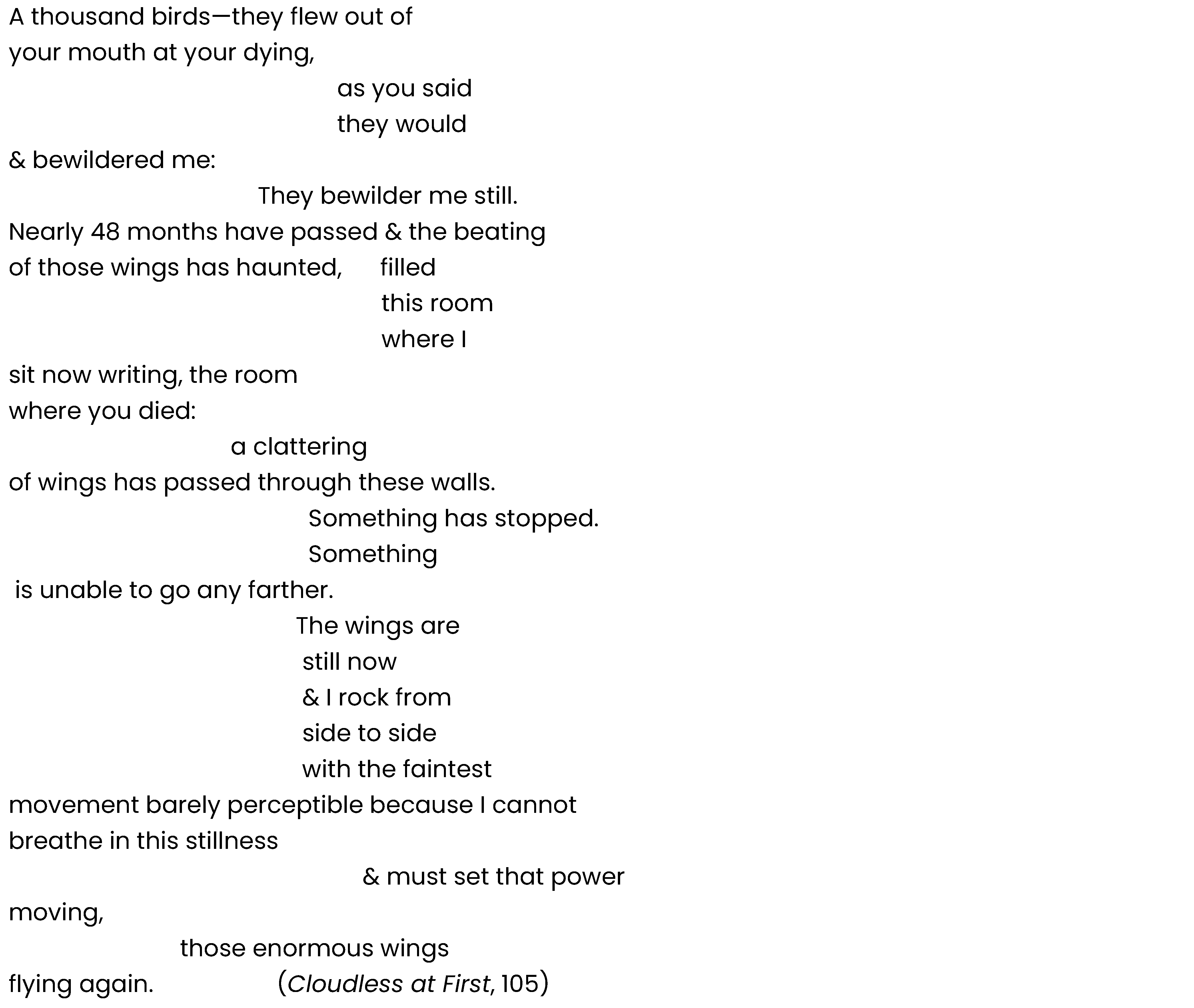

“A Thousand Birds” shows how effectively Morley spaces her lines for dramatic effect.

Her beloved has predicted that when he dies a thousand birds will fly from his mouth (“as you said / they would”). Far from comforting the speaker, their “clattering” wings prevent her from writing in the room where he died—a stillness in which she can’t breathe, can barely move. She “must set that power moving / those enormous wings / flying again.” The “power” is her creative gift, a gift she shared with Wolpe but which his death threatens: her will to write has stopped with his breathing.

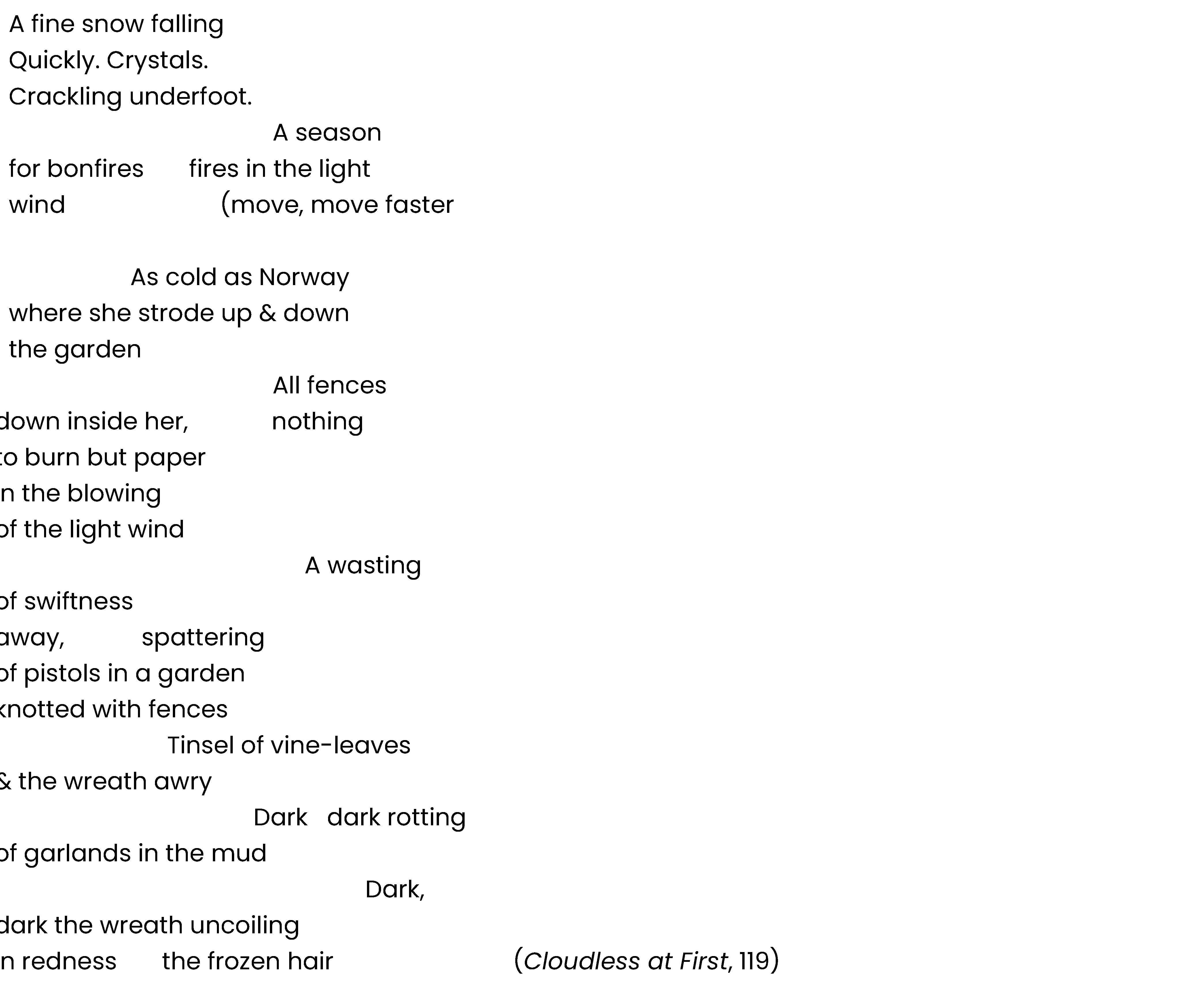

In another “organic” poem, Ibsen’s famous heroine is rendered, chillingly. Hedda

Using jagged half-lines as spare as a light wind, Morley suggests Hedda Gabler’s powerlessness, a “wasting of swiftness,” of meeting her fate in the garden with “all her fences down,” of her lover’s vine leaves rotting in mud, and after her suicide of a red “wreath uncoiling” around her frozen hair. The snow is fine and falling fast, but Hedda’s fate is moving even faster (“move, move faster”). By breaking the line after “A wasting” she emphasizes decay, not “swiftness,” which follows it; by breaking after “dark dark rotting” she stresses death, not “garlands,” which follows it. In the end there is no life in Hedda’s garden; it is as frozen as her hair.

Perhaps Morley’s greatest achievement—distilling all the pain of love found and lost, the terror of aging and living alone, and the surprise of renewal—is her poem “The Shutter Clangs” (To Hold in My Hand, 174). A meditation on Donne’s “Goodfriday, 1613. Ryding Westward,” it asks how she as an artist can integrate past and present. She remembers of Wolpe, “your diamond eye: / that precision tool / compounded of air & fire—a Venetian / eye” and feels herself torn between his memory (the East) and her future (the West). As she is pulled back by grief, she resists “saying / to myself—absent thee, / absent thee from felicity / a while—.” She needs to still the pain in order to tell her story.

How can she find courage to go on when her beloved, and most of her contemporaries, are gone? The “new . . . rises out of the mist” but will she meet it?

“The Shutter Clangs” treats the struggle to survive one’s losses, to free oneself from the “deaths / knives plunging / in unforeseeable places,” to lean into the distance with arms outstretched, to ride westward. But it also affirms how an artist transcends pain by using it. As in so many of her elegies, Morley poses the question of survival directly to her beloved:

Morley criticism is almost nonexistent, but in 1993 Brian Conniff reassessed the legacy of Black Mountain poetry in light of her work. As mentioned, Morley and Wolpe taught at the college from 1952–1956, although she was not only denied equal status, she was known as “Stefan Wolpe’s wife.” (For example, see Tom Clark’s Charles Olson: The Allegory of a Poet’s Life.) Conniff compares her marginal status—the worshipful treatment of Olson in an early tribute—to the self-sufficiency of her later poems, especially those that appeared in Cloudless at First (1988).

Like Levertov, Conniff recognizes how well Morley’s work exhibits Olson’s principle of kinesis: “One perception must immediately and directly lead to another perception.” He notes Morley’s “care and irreverence” for the past, that conflict she describes in “The Shutter Clangs” that fortifies her lines so that even when they describe a bird they are as volatile as quick-silver. She wants

Conniff also quotes one of Morley’s most intriguing poems about the creative process, “The Last Rehearsal.”

In this and other later poems, it is not ideas that renew the speaker, especially the speaker as artist, but joy in the physical world, in life as process, a refusal to bring down the curtain, and in fact to peek behind the curtain at the actors preparing their roles. In “With Cavafy,” Morley borrows a line from the Greek poet to explain how living “at a slight angle to the universe” allowed her to see more clearly. She could

Her separateness is more than shyness; it is a part of her identity, a bridge from fear of the unknown to “what was there to be made over.” This process of seeing the physical world from an odd angle with full awareness of what’s at stake is the subject of “Stop Look Listen.”

This stretching of the senses to “pull the world inside” requires constant shifting. Morley describes this act of consciousness in her statement of poetics in The Turning, where she compares the mind’s reactions to its world to her spacing of words on a page. Making art means paying attention to the “ticking, swirling, heaping, sliding” world.

Like so many New York poets of the 1950s, Morley paid attention—to the revolutionary ideas that swirled around her, to the (often unheralded) experiments of the painters and musicians she loved. She perfected the elegy as nature poem and prized friendships because they buffer the agony of loss. Morley’s elegies spring from senses awakened to the physical world by having loved Wolpe, “the man I loved / who made the imagination / more real & more so / than what the world calls real” (The Turning, 117). Once attuned to that world, her voice found its own music, her eyes saw “a blue-Leonardo sky” with light behind it.

Works Referenced by Hilda Morley

A Blessing Outside Us, preface by Robert Creeley. Woods Hole, MA: Pourboire Press, 1976.

Between the Rocks. Berkeley, CA: Tangram, 1992.

Cloudless at First. Mt. Kisco, NY: Moyer Bell, 1989.

“The Eighth Street Club” ed. Austin Clarkson, from On the Music of Stefan Wolpe: Essays and Recollections. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2003: 105–110.

To Hold in My Hand: Selected Poems, 19–1983, preface by Stanley Kunitz. New York, NY: Sheep Meadow Press, 1984.

Letter to Barbara and Francis Golffing. March 14, 1977.

“Music and Poetry,” Mid-American Review, v.10, n.2, 1990: 65–68.

Review of Martin Duberman’s Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community.

New Letters, v. 40, Winter 1973, 118–121.

The Turning. Wakefield, RI: Asphodel Press: 1998.

What Are Winds and What Are Waters, preface by Denise Levertov.

Cambridge, MA: Matrix Press, 1983. Wakefield, RI: Asphodel Press, 1993.

Additional Sources

Clark, Tom, Charles Olson: The Allegory of a Poet’s Life. NY: Norton: 1991: 229

Conniff, Brian, “Reconsidering Black Mountain: The Poetry of Hilda Morley.”

American Literature, v. 65, n. 1, March 1993: 124.

Creeley, Robert, “A Note for Hilda Morley,” preface to A Blessing Outside Us, Woods Hole, MA: 1976, Pourboire Press, np.

Kizer, Carolyn, “The Light of Hilda Morley,” in Proses. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 1993: 160.

Stanley Kunitz, “Where Joy Is,” preface to To Hold in My Hand, Sheep Meadow Press, NY: 1983: np.

Denise Levertov, preface to What Are Winds and What Are Waters, Matrix Press, 1983. Cambridge, MA: 1993, np.

Cite this article

Mullenneaux, Lisa. “Hilda Morley: Lost on Black Mountain.” Journal of Black Mountain College Studies 15 (2024). https://www.blackmountaincollege.org/journal/volume-15/mullenneaux.