Jonathan Williams’s identity as a gay man is interconnected to his practice as a portrait photographer, a practice he developed at Black Mountain College from 1951 to 1956.[1] Williams documented artists and writers, and, when read alongside the biographical literature on queerness at Black Mountain,[2] these portraits act as psychological snapshots into a season of becoming that arguably could not have occurred at other American art schools. Working with a medium format camera during the height of the McCarthy years,[3] Williams’s photography provided a mode of self-fashioning for a group of gay men that countered homophobic discourses present on campus. Despite Williams’s antipathy towards labels like “homosexual,” “Black Mountaineer,” and even “photographer,” his photographs prove formative within the collective queer memory of the College. This article traces the development of Williams’s photography during his years at Black Mountain.[4] My analysis extends beyond the mainstream narrative to incorporate an alternative social history of BMC. Through this framework, I argue that Williams’s portraits fostered a deeper sense of self for his queer circle and serve as visual evidence for their confessed experiences.

As the founder of his own publishing imprint, The Jargon Society, and a contributing editor and writer of Aperture,[5] Williams promulgated his ideas on photography through poetry and prose.[6] Although he quotes Ralph Steiner’s statement, “No person writing on photography has ever said anything that helped me do better on Thursday what I’d done less well on Wednesday,”[7] in his essay “The Camera Non-Obscura,” Williams was not disinclined to lend his advice on the medium. In the same essay, he urges collectors to “Avoid Big Names. Irving Penn, Walker Evans, Bill Brandt” and to “seek out the photographers your own age and collect what moves you.”[8] Williams’s fragmented essay is unified by the point that photographers and poets work under similar means of extraction, re-presenting the people, places, and things of our everyday in a divine light to a select group. “Poets and photographers do not necessarily believe in public audiences or constituencies. They believe in persons, with affection for what they see and hear. They believe in that despised, un-contemporary emotion: tenderness.”[9] While “’photographic talk’” could “bore the tits off a hog,”[10] Williams’s excitement for photography stemmed from the photograph’s ability to revive shared memories between him and his friends, as well as for the capability of conversation to ascribe new meaning to the image.

Recent literature on Williams centers on his role as an independent publisher and writer, proponent of overlooked artists and poets, and a photographer in his own right, but his participation in the expansion of queer photographic language deserves rightful investigation. Richard Deming published an essay on Williams in 2009, “Portraying the Contemporary—The Photography of Jonathan Williams,” in which he argues that Williams’s portraits forged community for the artists he depicted in their early careers. Deming proposes that Williams’s photographs are both public and private; that the relationship between Williams and his subject “is of paramount importance” and so too is the universality of “communicable tenderness” portrayed in his work.[11] He astutely questions Williams’s motives for taking up portraiture:

If a photograph enacts the photographer’s identity, becoming the screen by which to discover how he or she sees, then are we to see the images as being Williams’ desired reality—that is, the photographs become allegories of his desire—or was this a reflection of Williams’ own complex versions of how to be both masculine and gay?[12]

Deming continues: “These questions are not easily resolved to be sure. . .”[13] But I find that an inquiry into Williams’s gay experience at Black Mountain can provide answers. While Deming is right to analyze the affection of Williams’s portraits of the unsung in the avant-garde, there is still much to be said on the queer social context that surrounds his Black Mountain portraits. Mobilizing Deming’s notions that Williams’s camera “conveys authority,”[14] and that the self emerges in portraits of others, can we ask how Williams reconciles his queer self through his portrayals of his BMC circle? In addition, how does the meaning of his portraits change when viewed through a divergent history as told by his subjects’ oral and written testimonies?

Male homosexuality at BMC remained a sensitive subject throughout the institution’s lifespan. Will Hamlin, a student at Black Mountain from 1940 to 1943, wrote in an unpublished memoir that “If there were homosexual relationships during my time at the college . . . they were very closeted.”[15] In June 1945, the drama professor Robert Wunsch was arrested for “crimes against nature” after being caught with a man in his car.[16] The event remained in the memory of the College well after Wunsch resigned, as mentioned by Michael Rumaker who studied alongside Williams and other Black Mountain poets from 1952 to 1955.[17] “Quieter” instances of homosexuality occurred at BMC following the Wunsch debacle. During the summers of 1948, 1952, and 1953, John Cage and Merce Cunningham taught at the College but never revealed their relationship publicly, although many at the College gossiped about it.[18] Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly’s relationship budded by the summer of 1951; the two posed nude for figure drawing classes.[19] Lou Harrison, who Williams photographed on numerous occasions in and out of Black Mountain, taught music during the 1951 Summer Session and through the spring of 1952.[20] Rumaker wrote that Harrison “was obviously gay” but that he “kept his distance.”[21] Although the College had come a long way in acceptance since Wunsch, outward expressions that challenged sexual norms remained denigrated, evinced by the expulsion of Paul Goodman for his controversial lectures on sexuality and flirtation with male students during the summer of 1950.[22] Mary Emma Harris writes, “There had always been homosexuals at the college, but Goodman made homosexuality, and his own sexuality in particular, an issue.”[23] Queerness could exist at Black Mountain, but it had to remain contained.

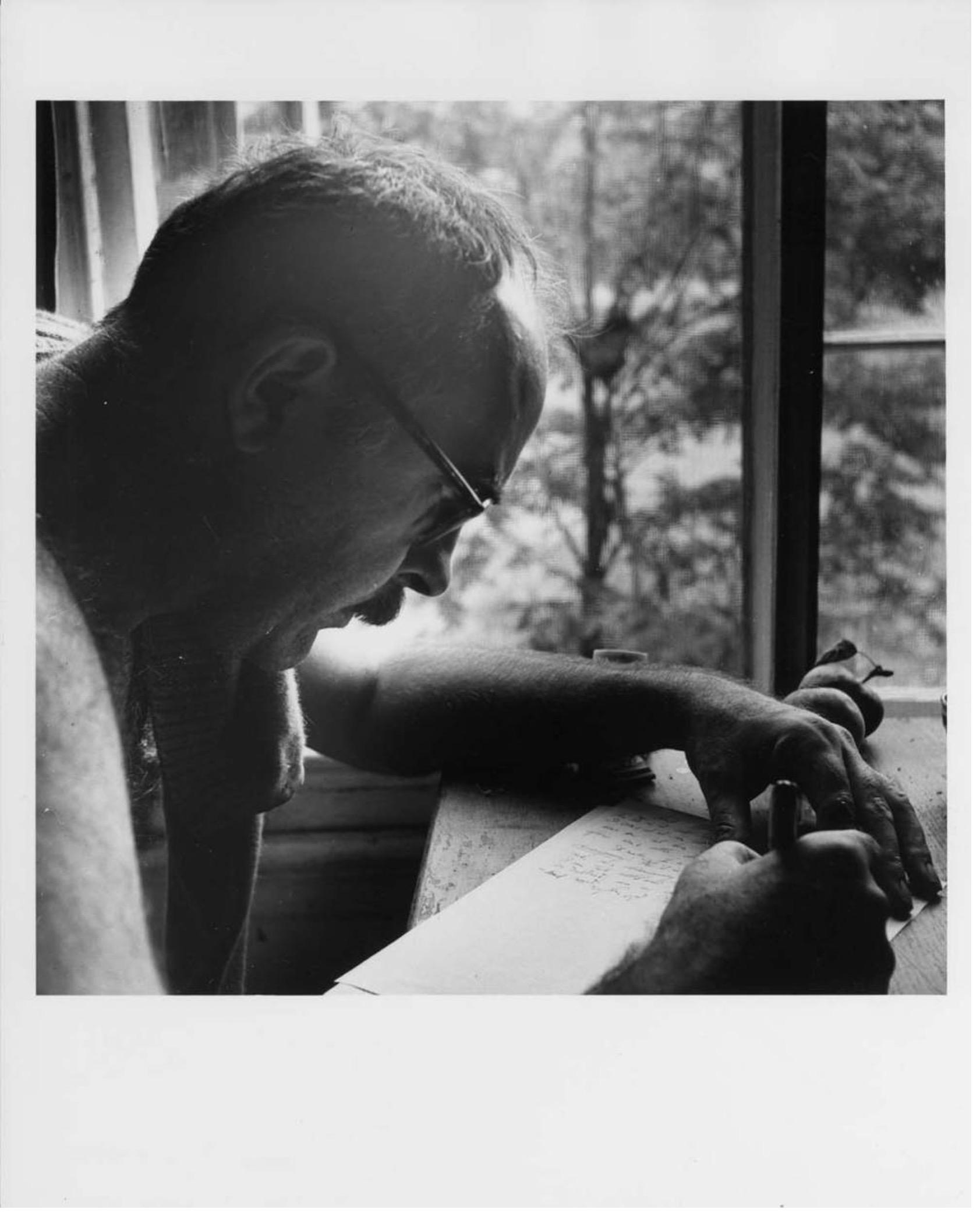

Williams first heard about BMC from M.C. Richards on her visit to the Institute of Design in Chicago (ID) in 1951 to stir up publicity for the College, where Williams was studying graphic arts under Hugo Weber and Harold L. Cohen.[24] After expressing interest in Black Mountain, Harry Callahan informed Williams that he would be teaching courses in photography alongside Aaron Siskind for the 1951 Summer Session. Williams was not able to enroll in Callahan’s course at ID, so he followed him to Black Mountain.[25] Williams also recalled that Chicago “was a gloomy time for sex,”[26] leading one to assume that photography was not the only driving factor to go to Black Mountain. At BMC, he learned the controls of the Rolleiflex under Callahan and Siskind. The square format would stick with him for the rest of his life, only working with the Rollei, Hassleblad, Mamiyaflex, and Polaroid SX-70 and allegedly never a 35mm.[27] BMC did not spark his interest in photography, as he had previously visited Gallery 291 in New York City and conversed with Alfred Stieglitz and the landscape painter John Marin.[28] However, he claims that he “had yet to pick up a camera” until BMC.[29]

Siskind and Callahan’s photography classes at Black Mountain were flexible and taught in cooperation “on a workshop basis.”[30] Williams told Martin Duberman in November 1968 that “occasionally there’d be a sort of class critique where everybody’d bring in the stuff they’d been doing for the week. He and Callahan would sit there and discuss it all and we’d continue the conversation at Peak’s.”[31] Not having a set schedule for coursework followed a rule espoused by Charles Olson, the rector of the College after the Alberses departure, to “never be rushed.”[32] Williams adopted this approach, taking time to frame each of his photographs as carefully as his prose.

Olson’s largest impact on Williams and other student poets was his philosophy of finding one’s voice. A particular statement by Olson during his first semester stuck with him: “The artist is his own instrument.”[33] Williams later elaborated, “You’ve got to manufacture yourself. America’s like that.”[34] One way Williams acknowledged Olson’s sentiment was by founding The Jargon Society, a method of usurping agency from the pernicious American publishing world. Another way was through photography. By photographing himself and his circle, Williams took control of his group’s representation.[35] That is not to say that Williams was concerned with how the outside world perceived them, but rather how he and his friends viewed each other. Williams recalled:

. . . you started from your friends. I mean you started from the community, those whom you should reach first were obviously the people around you. So we’d produce these things, and not big editions at all – maybe 50 copies would satisfy the demands of the College. That’s still, essentially, why I make Jargon books, to satisfy the demand of a kind of community which doesn’t exist in fact but exists in people’s heads.[36]

As both a publisher and photographer, Williams’s production sought to foster togetherness, supplying his friends with unique objects and images they could call their own.

Williams first encountered the camera’s potential for self-fashioning at BMC. Portraiture allowed him to examine and expose the homoerotic relationships suppressed by the guise of masculinity at Olson’s Black Mountain.[37] If we follow Ross Hair’s argument that Williams’s queerness set apart his verse from the Black Mountain Poets, we can extend this interpretative framework to his photographs as well. Upon analysis of memoirs, correspondence, and interviews, a realm of queer intimacy presents itself in Williams’s portraits. Relying on this source material might raise concerns of historical accuracy.[38] However, as Gavin Butt notes, “. . . gossip, though often dismissed as idle or small talk, was socially important for gay men in the fifties and sixties for conveying information which evaded the discursive taboos around homosexuality afflicting official modes of communication.”[39] By acknowledging the insights into Williams’s social relations that can be found in these sources, his portraits provide a reciprocal form of visual material that lays truth to his college circle’s queer experiences and desires—memories that risk being sidelined in the dominant BMC narrative.

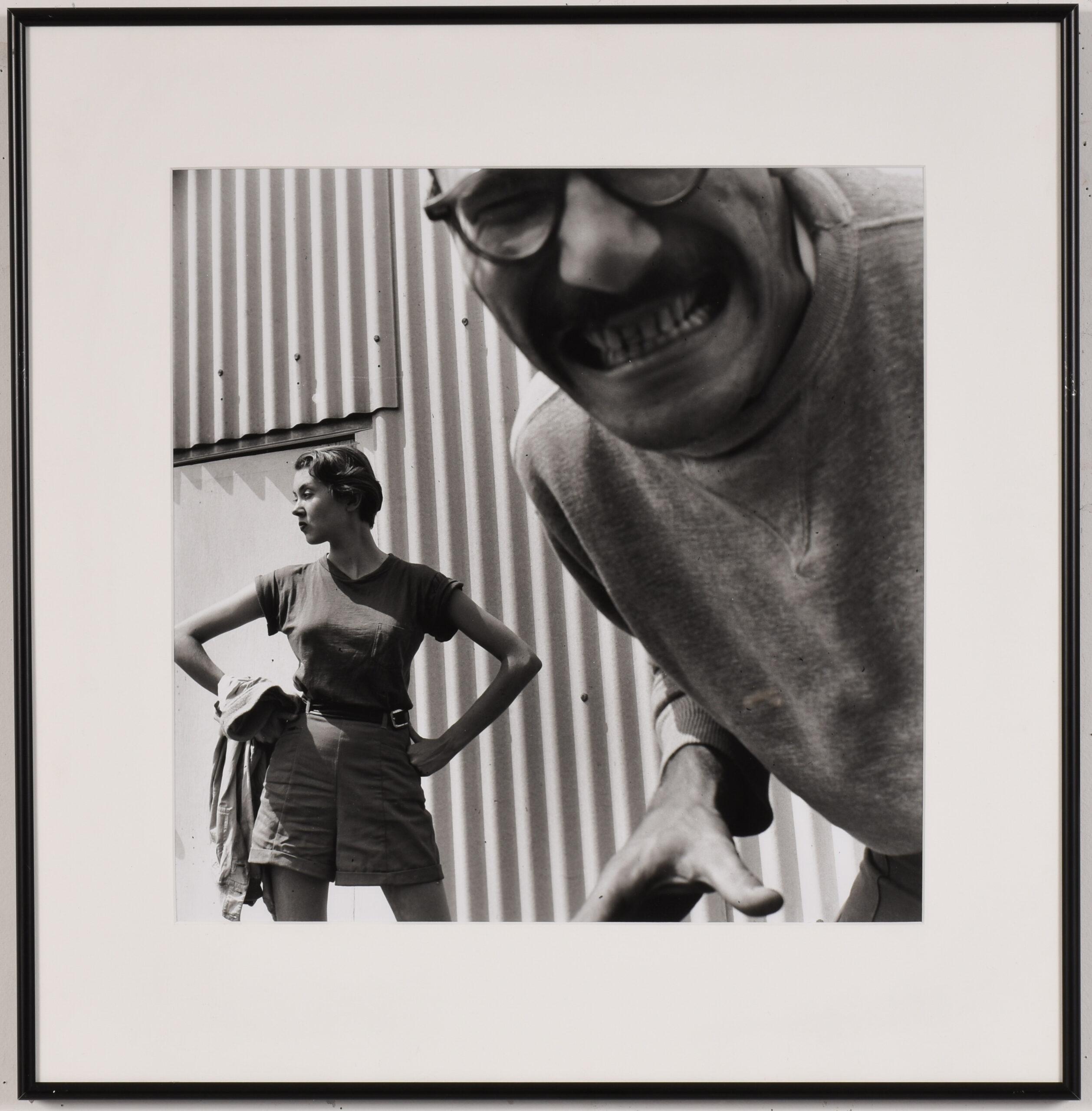

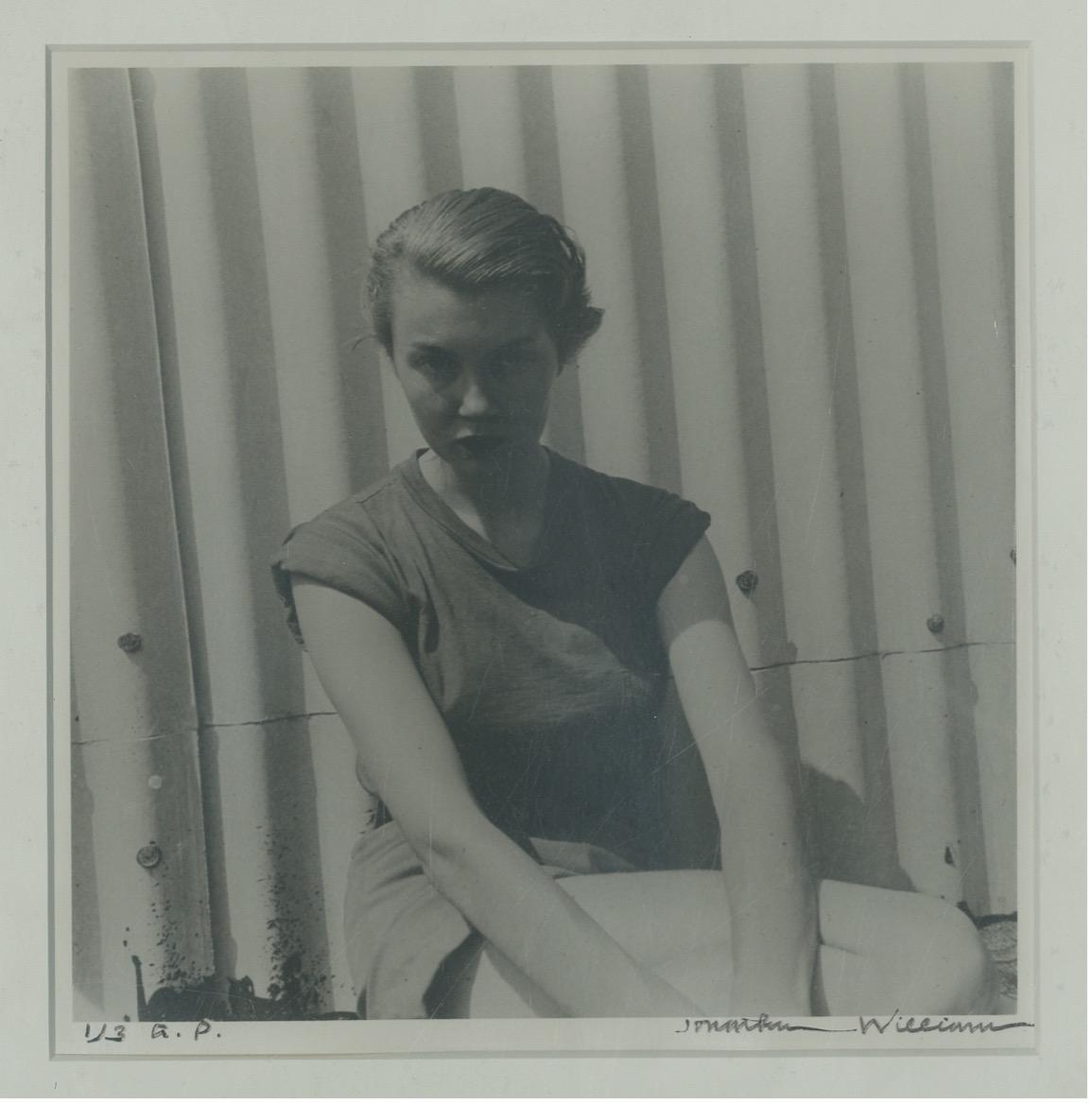

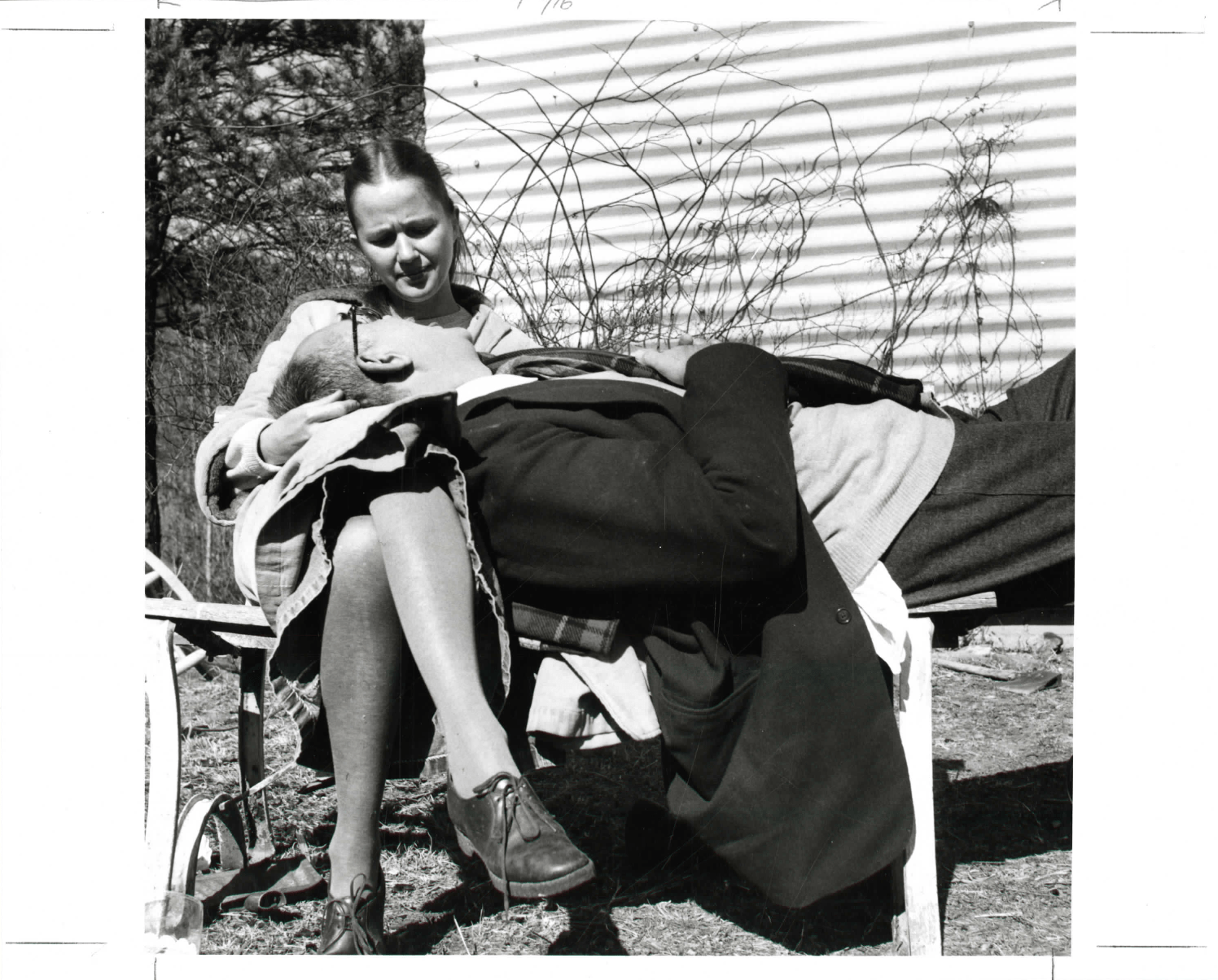

Consider Williams’s portraits of Francine du Plessix Gray (Figs. 1 and 2), taken during the Summer Session of 1951.[40] Viewed as a series, Gray represents the point of Williams’s interest. Williams focuses on Gray’s sharp confident expression rather than on Oppenheimer’s grimacing face in the foreground. He moves inward, framing Gray askant against the corrugated sheet metal of the sundeck of the Studies Building. That summer was formative for Gray, who reflected on the session in 1987:

Supercool prose of silence or monosyllabic utterances, bare feet, men’s dark glasses and long hair, easygoing nudism and bisexuality—fads of the just nascent Beat Generation, precursors of the 1960s Movement style. (I hadn’t skimped on Black Mountain’s brand of unisex macho, chopping off my hair as short and jagged as contemporary punk’s.)[41]

Gray was a rebel at Black Mountain and, as Williams recalls, thought Charles Olson “was a total crock . . . They were great antagonists.”[42] To challenge Olson at Black Mountain was daunting, especially for a female student, but Gray was up for the task.

Figure 1: Jonathan Williams, Beauty and the Beast (Francine du Plessix Gray and Joel Oppenheimer), 1951. Gelatin silver print, 21 3/4 x 21 1/4 inches. Collection of Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center. Gift of the Artist.

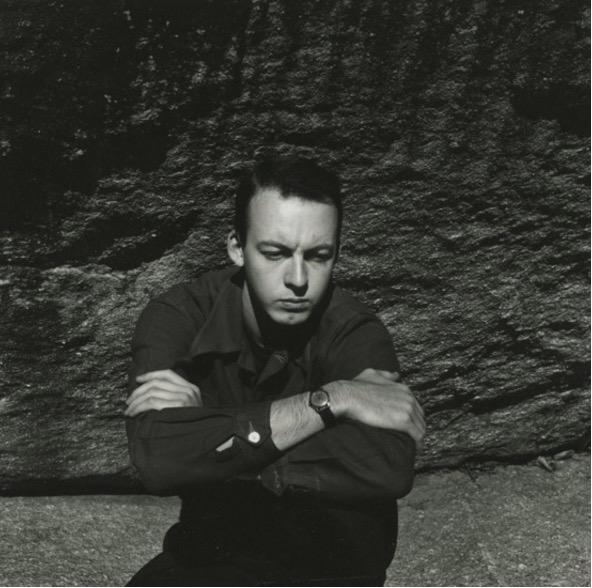

Around this time, Gray took a portrait of Williams nearby at his family home in Highlands, NC. The two were in a relationship,[43] which Williams noted was the first time he had ever seriously been with a woman.[44] “I made it with girls and I made it with boys,” and there was “a lot of healthy confusion,” as he put it.[45] Gray’s portrait of Williams captures this “confusion.” The square image shows Williams taking a knee in a squat three-quarter pose against a boulder (Fig. 3). Williams’s expression is tense, with his furrowed brow and protectively crossed right arm as he crouches in the dark. He looks outside of the frame with a sense of concern for the future, complemented by his wristwatch as a symbol of passing time. The slight shadow cast across his face heightens the somber drama of his gaze. Comparing these two formalized portraits of Gray and Williams, her confident and subtly intimidating stare sharply contrasts with his uncertainty for what is to come.

Figure 3: Francine du Plessix Gray, Jonathan Williams, Middle Creek Falls, Scaly Mtn., North Carolina, 1951, Gelatin silver print, 5 7⁄8 x 5 7⁄8 inches. Image obtained from Jonathan Williams: The Lord of Orchards, ed. Jeffrey Beam and Richard Owens (Westport and New York: Prospecta Press, 2017).

Williams stayed at Black Mountain for one semester before being deployed in January 1952. He spent seventeen months in Stuttgart, where he had a relationship with another woman which he recalled was “a rich and awkward experience.”[46] He returned to Black Mountain around January 1954, stayed through the summer, and then travelled to San Francisco in October, where his queer identity blossomed. He spent considerable time with Robert Duncan, an openly gay poet who would later come to teach at Black Mountain in 1956, and at The Place, a bohemian bar and arts venue opened by former BMC students Knute Stiles and Leo Krikorian:

I spent most evenings at The Place on Grant Street in North Beach, the best place of its kind I ever went to in America. It was bohemian, not gay, not straight, not simply anything. I met Ginsberg there. There were painters, musicians, intellectuals. Some wanted sex—a good way to finish a cultivated evening talking about the end of Charlie Parker, or the play of the San Francisco baseball team, or the Zinfandel grape, or Duncan’s new play.[47]

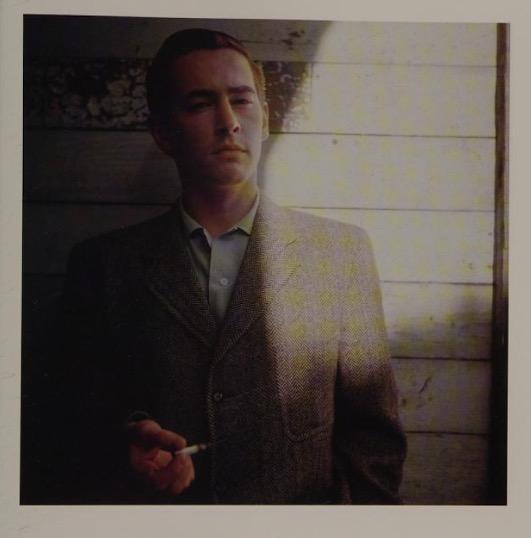

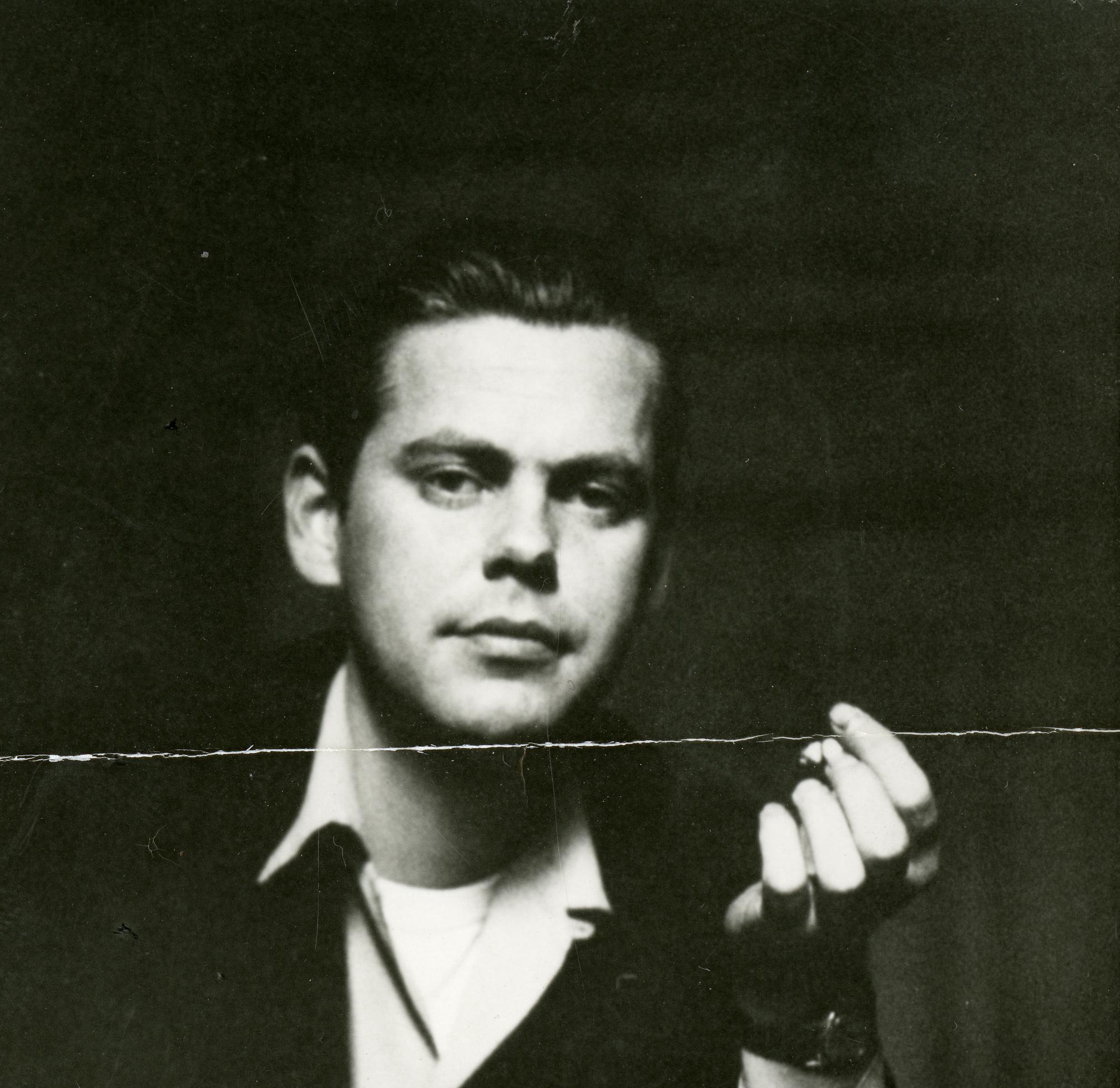

While in SF, Williams also met Michael McClure, a poet who Williams would later publish. McClure was not gay, but Williams was “enamored” with him and reports hiding his attraction from him. Williams photographed McClure that summer on color film (Fig. 4). The framing is like his portraits at Black Mountain: at medium-distance, against a nondescript structure, and accentuated by a beam of natural light. The flaking white paint of a plank acts as a compositional tool that draws our attention to his gaze; the only variation in the blank background, aligned with his eyes. His lower right hand reaches out from a corner of tenebrosity, unfocused but defined. Later publishing the photograph in A Palpable Elysium, Williams writes, “I used to call him ‘Allure’ McClure. Neither Allen nor I ever got anywhere, anywhere at all. I once sequestered (i.e., stole) his undershorts in a cabin in Carmel Highlands and kept them as a sacred erotic object.”[48] Not only did Williams return to Black Mountain with a newfound awareness of his gay identity, but he also became aware of the erotic sensibilities one could attribute to photographs, like a stolen pair of underwear.

Figure 4: Jonathan Williams, Michael McClure, San Francisco, 1954. Image obtained from Jonathan Williams, A Palpable Elysium: Portraits of Genius and Solitude (Boston: David R. Godine, 2002) p. 119.

Upon return to Black Mountain College in the spring of 1955, the poet Robert Creeley was now teaching on campus. The two collaborated on numerous publications together, publishing one small but notable book, All That is Lovely in Men, composed of twenty-six poems by Creeley and abstract drawings by Dan Rice, another Black Mountain peer, printed in an edition of 200 for $2.50 per copy. Rumaker recalled that Creeley and Rice “were like twins, inseparable.”[49] Duberman writes, “some thought the only way to describe these two wholly heterosexual men, was as ‘lovers.’”[50] As Williams later noted to Duberman, the book was “bought erroneously by a few homophiles and an increasing number of friends.”[51]

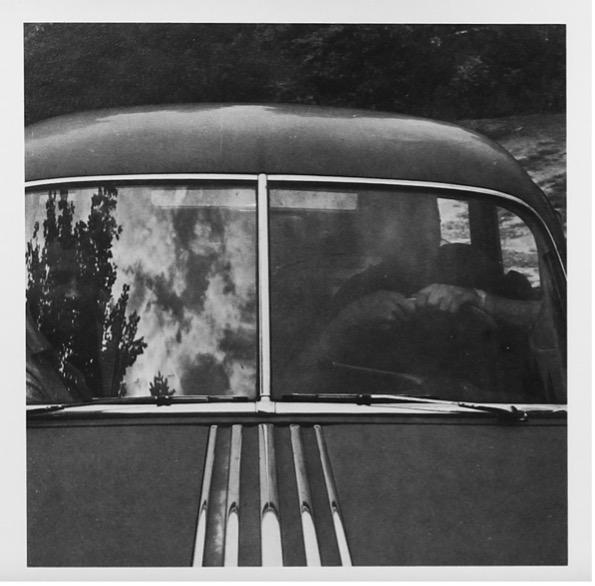

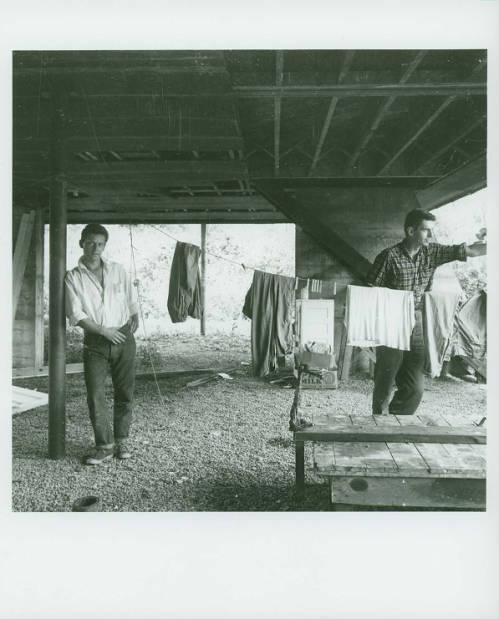

The cover features a photograph by Williams of Creeley and Rice in a car (Fig. 5), which was chosen from other photos that he snapped of the duo.[52] As a group, these images present a play between the two men in a non-macho, camp fashion. The most well-known photograph from this shoot (reproduced on the cover of Duberman’s Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community) depicts Rice peeping out of a barrel and Creeley sitting on a discarded toilet, mimicking the image of Christ seen in the reproduction of Vittore Carpaccio’s The Meditation on the Passion in the background (Fig. 6). Another photograph shows Rice and Creeley with clothes drying on a line under the studies building, hinting at a sense of domesticity between the two men (Fig. 7). A further photo shows the two playing on a playground (Fig. 8). Rice, with his shirt unbuttoned slightly revealing his torso, stares at Creeley with charming affection.

Figure 5: Jonathan Williams, Robert Creeley and Dan Rice at Black Mountain College. Image obtained from Aggie Weston’s Ten Photographs by Jonathan Williams, p. 3.

Figure 7: Jonathan Williams, Robert Creeley and Dan Rice at Black Mountain College, 1955. Courtesy of the Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina.

At this time, Creeley and his wife back in Mallorca were splitting up and he had a reputation across campus for emotional breakdowns.[53] Compared to Williams’s photograph of Robert and Ann Creeley in Mallorca (Fig. 9), the emotional attachment between Rice and Creeley at Black Mountain reads as more subdued. Rumaker speculates “Perhaps that summer spent close to Dan was for Robert an actualization of a past fiction. The poignancy of forgetting, in all our upbringings of rigidly enforced heterosexist determinations . . ..”[54] The emotional and sexual reckoning comes out in the poem from which the Jargon book derives its title:

Nothing for a dirty man

but soap in his bathtub, a

greasy hand, lover’s

nuts

perhaps. Or else

something like sand

with which to scour him

for all

that is lovely in women [55]

The interplay between the final line and the book title points to the fluidity of sexuality at 1950s Black Mountain. Does Creeley love women, or does he love men? Williams group portraits present a case for the later, lending evidence to Rumaker’s supposition, however fantastical.

Figure 9: Jonathan Williams, Robert and Ann Creeley, 1953. Image courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York. https://digital.lib.buffalo.edu/items/show/83852.

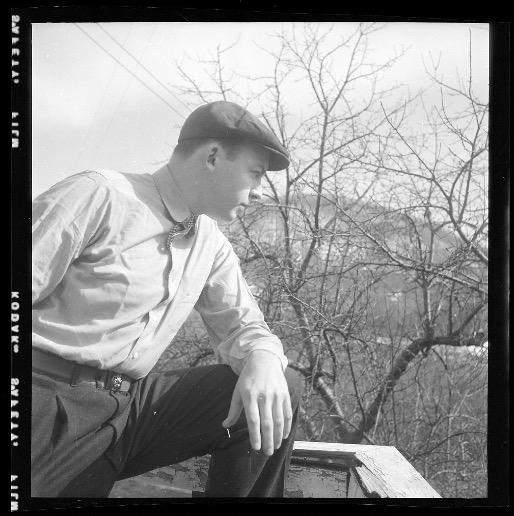

That same year, Williams took a self-portrait while standing in the corner of the sundeck (Fig. 10).[56] He is looking out over the woods, with his arm propped on his leg as if he is a captain of a ship looking out from the stern. Compared to his portrait by Gray, Williams appears more confident in his place at Black Mountain (he had recently published Olson’s Maximus Poems to student and faculty praise). His attire contrasts sharply with the dress of everyday students at BMC, pointing towards the effort he put forth in presenting himself to the camera and his community.[57] The concise framing mirrors his fresh haircut, pressed shirt, and dignified pose. The telephone wires in the background run parallel to his line of vision and converge in front of his eyes, complementing his sharp focus. Photography has become a tool for Williams’s self-presentation.

Figure 10: Jonathan Williams, Self-Portrait, ca. 1955. Jonathan Williams Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

At this point, Olson and his wife Constance, “a cohesive force in the community,” are about to separate due to his affair with another student.[59] Williams himself had to travel with her to New York when she left Black Mountain.[60] Michael Rumaker, who once came across Olson nude in his home, recalls his questioning of Olson’s sexuality: “that if he were queer it would have instantly shattered my respect for him, my admiration, the deep need for his acceptance, I was so poisoned.”[61] Although Olson negatively impacted the bind of the community with his sexual life, as too did the founder John Andrew Rice when his affair with a student came out in 1938,[62] there was still a desire to conceal one’s homosexuality from his eyes. Olson’s insecurity in his own sexuality comes out in a letter he wrote to Robert Creeley after Robert Rauschenberg almost drowned one night in Lake Eden in January 1952:

But there were signs which began to bring the whole incident down from the pitch of the moment under the pine tree before I even saw the story in the water, to the muddiness of the underlying homosexuality, to the normalness of these people, from which, when I finally left, I turned away. And from which I rise with such effort today.[63]

To be depicted as queer would be Olson’s downfall. In Williams’s later portraits, he now covers himself, his body against the queer gaze, yet Williams sees through. Another photograph from the 1955 shoot shows Charles laying his head in Constance’s lap (Fig. 14). Williams captures Olson in an affectionate and vulnerable moment that subverts his teacher’s paternal position. Williams recalls that it took him “a long time to get out from under Leviathan J. Olson,” the teacher who informed his “whole poetic vision” and “whole vision of life.”[64] Taking Olson’s portrait, framing him through his own lens, within his own identity, was surely one way of doing this.

Figure 14: Jonathan Williams, Charles Olson with Constance Olson (his head resting in her lap), ca. 1953-1955. Box 323, Folder 49. Charles Olson Research Collection. Archives & Special Collections at the Figure 27: Jonathan Williams, Unidentified Man, ca. 1978-1995. Polaroid. Jonathan Williams

Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.[65]

Around the time the College folded, Williams took an intriguing portrait of Fielding Dawson (Fig. 15), an artist and writer who he met on campus and who he would collaborate with on future Jargon publications.[66] At surface level, the photograph is an unremarkable document of a potential moment at Black Mountain.[67] However, the underexposed and damaged print is illuminated by the provenance, as well as the stories told by Williams, Meyer, and Dawson.[68] According to Thomas Meyer, Williams and Dawson had a close relationship at Black Mountain during Williams’s first semester at Black Mountain; Francine du Plessix Gray allegedly caught them in bed and pulled Williams out.[69] Dawson’s portrait remained in Williams’s personal collection for decades, like a photograph in a family album. The scratches and fold that lacerate the print heighten the familiarity of the photograph, an object to be handled, viewed, and passed around in Williams’s Highlands residence. Dawson wrote a memoir on his experience at Black Mountain College, The Black Mountain Book, in which he recounts his same-sex encounters with unnamed students. In the revised edition, he writes, “No one has gone into the detail it deserves, of the homosexual period at the school which lasted from spring 1950 to the summer of 1952. A vivid, untold story.”[70] Williams’s photograph of Dawson aids the resurgence of this narrative, as the memory of their relationship at BMC reframes the image as a product of intimacy.

Figure 15: Jonathan Williams, Fielding Dawson, ca. 1955. Image courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York. https://digital.lib.buffalo.edu/items/show/83551.

After departing Black Mountain in 1956, Williams maintained connection with the writers he collaborated and socialized with at the College. In an interview, he states “The arts are nothing more than a community. Now Black Mountain was a place and time, in fact. After we left it, most of us who were nurtured by it, have made our own community for ourselves.”[71] Adopting this lesson in community formation, many of the homosexual writers and artists at Black Mountain migrated to San Francisco during the declining years of BMC, pulled to the Bay by the allure of the emerging Beat Generation and perhaps the stories told by Williams.

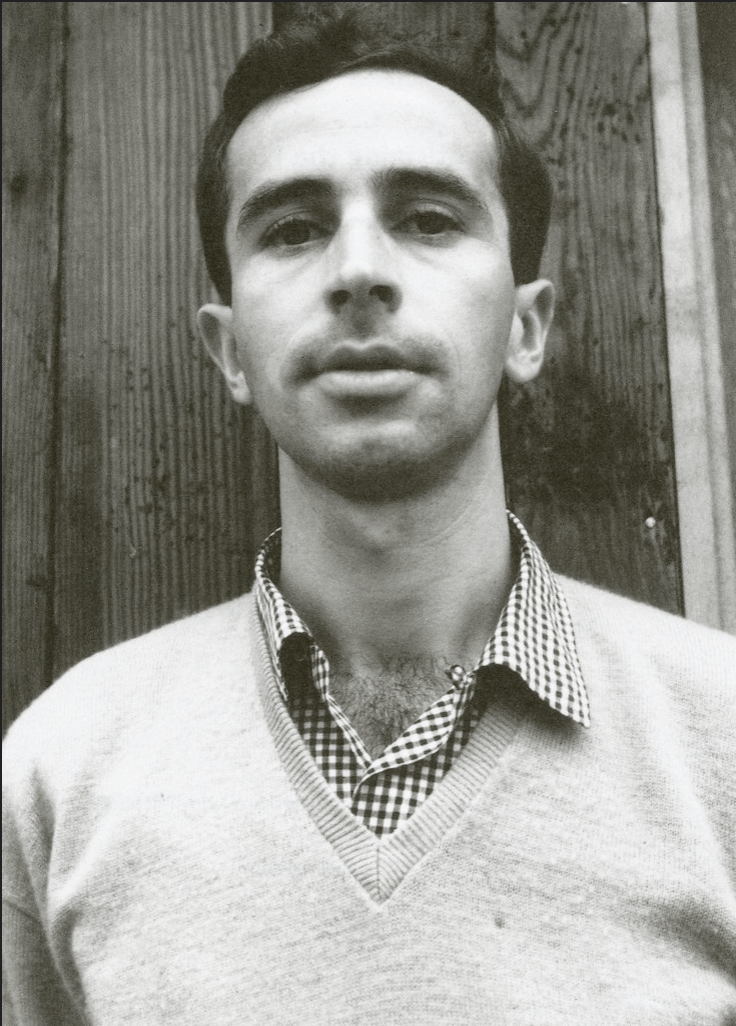

Shortly after hitchhiking out west to SF, Michael Rumaker posed for a portrait in Sausalito, California by Williams (Fig. 16). Although the format does not match Williams’s preference for the square, Rumaker is framed against a bare background and within a tight medium-range composition like Williams’s other Black Mountain portraits. The camera’s tilt adds a sense of depth to Rumaker’s slight downward gaze. The complementing V’s of Rumaker’s sweater and shirt draws our eye to his exposed chest hair. This seemingly simple portrait is affected by Rumaker’s full account of his college experience in his memoir Black Mountain Days. Not only did Williams set up Rumaker with friends in New Orleans, where Rumaker traveled to escape a period of “sexual drought at Black Mountain,”[72] he also to took him skinny dipping one night after a campus party, which Rumaker cut short due to the overbearing fear of being spotted by locals, “hidden in those trees, eyes watching us, two men lying naked together.”[73] Rumaker’s time at Black Mountain was formative, as it was the first time he was open with a man and the site of his suicide attempt. He graduated with honors in 1955 and returned for a brief visit in 1956, where Williams was present and when he began planning to move to SF.[74] Like Williams, Rumaker also developed his approach to portraiture at Black Mountain. Rumaker wrote to the graduate committee in 1954:

In the months that followed [after arriving at Black Mountain], I wrote over a half-dozen or so of these ‘portraits’, and finally, after going over them and reading them outloud to myself, I discovered a very funny thing. These stories of people who interested me so much turned out, for the most part, to be little more than actual portraits of myself, and very badly disguised, at that. I had always thought previously that it was a sin or vanity to write about yourself. But seeing then that I would come through despite unconscious attempts at camouflage, I now recognize the futility of resisting it any longer, and, therefore take me to be the subject.[75]

At Black Mountain, Rumaker realized that if he concealed his true self, that it would always emerge in his depictions of others, and that he could not capture a person’s essence until he was honest with himself. Williams’s portrait of Rumaker follows along this line of queer integrity, to look inward before looking outward. The shadow, deeply casted across the faces of many of Williams’s BMC portraits, has now been lifted.

Figure 16: Jonathan Williams, Michael Rumaker in Sausalito, California, 1956.

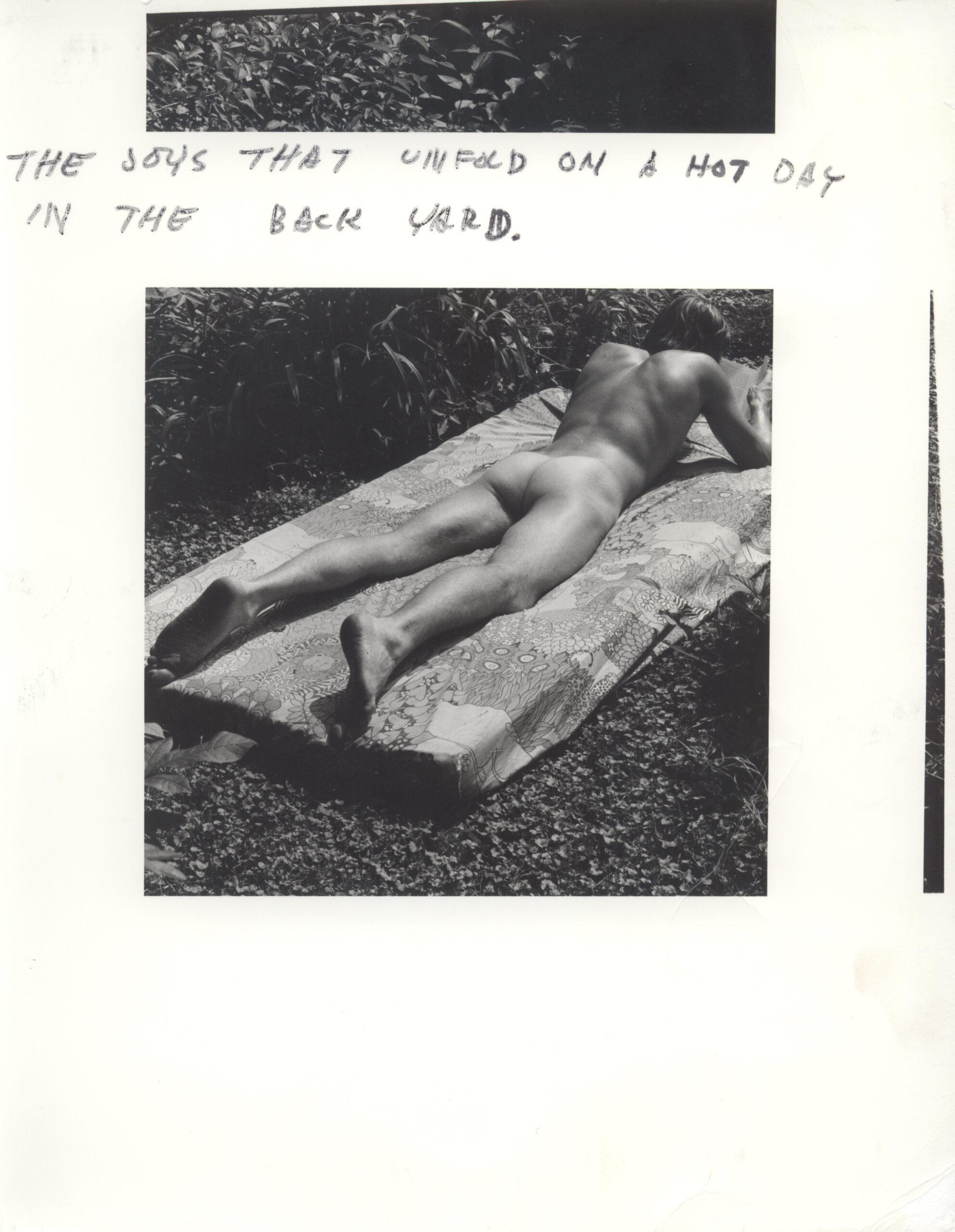

Portrayals of queerness become more apparent in Williams’s work following his departure from BMC, both in his poetry and photography. He wrote to Louis Zukofsky on March 4, 1958: “I’ve got a couple new pastorial love-type pomes [sic], but they sound so much like RD [Robert Duncan] (or, I suspect they do) I’m keeping them to home.”[76] A set of photographs from around this time of an unidentified man, nude and sprawled out in the outdoors mirrors the content of “pastorial love-type pomes.” Williams peers at the man’s backside, slightly censored by the foliage in the foreground, as he reads and smokes (Fig. 17). His veins bulge along the wrist of his hand keeping his place on the page. The towel peeking in from the lower corner heightens the eroticism of the scene. Using photographs from this outing, Williams experiments with the cropping of the image and text on a page (Fig. 18). Now showing the man’s exposed rear, Williams writes “THE JOYS THAT UNFOLD ON A HOT DAY IN THE BACK YARD” in the negative space of the superimposed grid. He later remarked that “I’ve always found that you couldn’t ‘illustrate’ poetry but that you could take the work of a photographer and set it next to the work of a poet and make a sort of new thing.”[77] Williams incorporates his writing and photography to instill a moment of queer joy in his own backyard. The interplay between poetry and photography mirrors Black Mountain’s central pedagogy of experimenting across media, but the content—the male nude in a mountain landscape—recalls his gay experiences at the once nearby College.

Figure 17: Jonathan Williams, Unidentified Man, ca. 1958. Image courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York. https://digital.lib.buffalo.edu/items/show/83536.

Figure 18: Jonathan Williams, Unidentified Man, 1958. Image courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, the State University of New York. https://digital.lib.buffalo.edu/items/show/83537.

After Williams met Thomas Meyer in 1968, the couple retreated from urban life in the early ‘70s, splitting their time between homes in Highlands, NC and Corn Close, England. Williams and Meyer’s home life interested various queer circles, reminiscent of Robert Duncan and Jess’s life in SF, to which Williams hailed Duncan as “the bard of gay domesticity.”[78] Irritated by the troubles of frequent travel with his past lover Ronald Johnson, Williams wrote to Jess from Vienna on May 29, 1966: “It would be glorious to settle down into a landscape with waterfalls, mountains, and gardens.”[79] Although Meyer and Williams would still frequently travel, their secluded homes provided a sanctuary to live, work, and love.

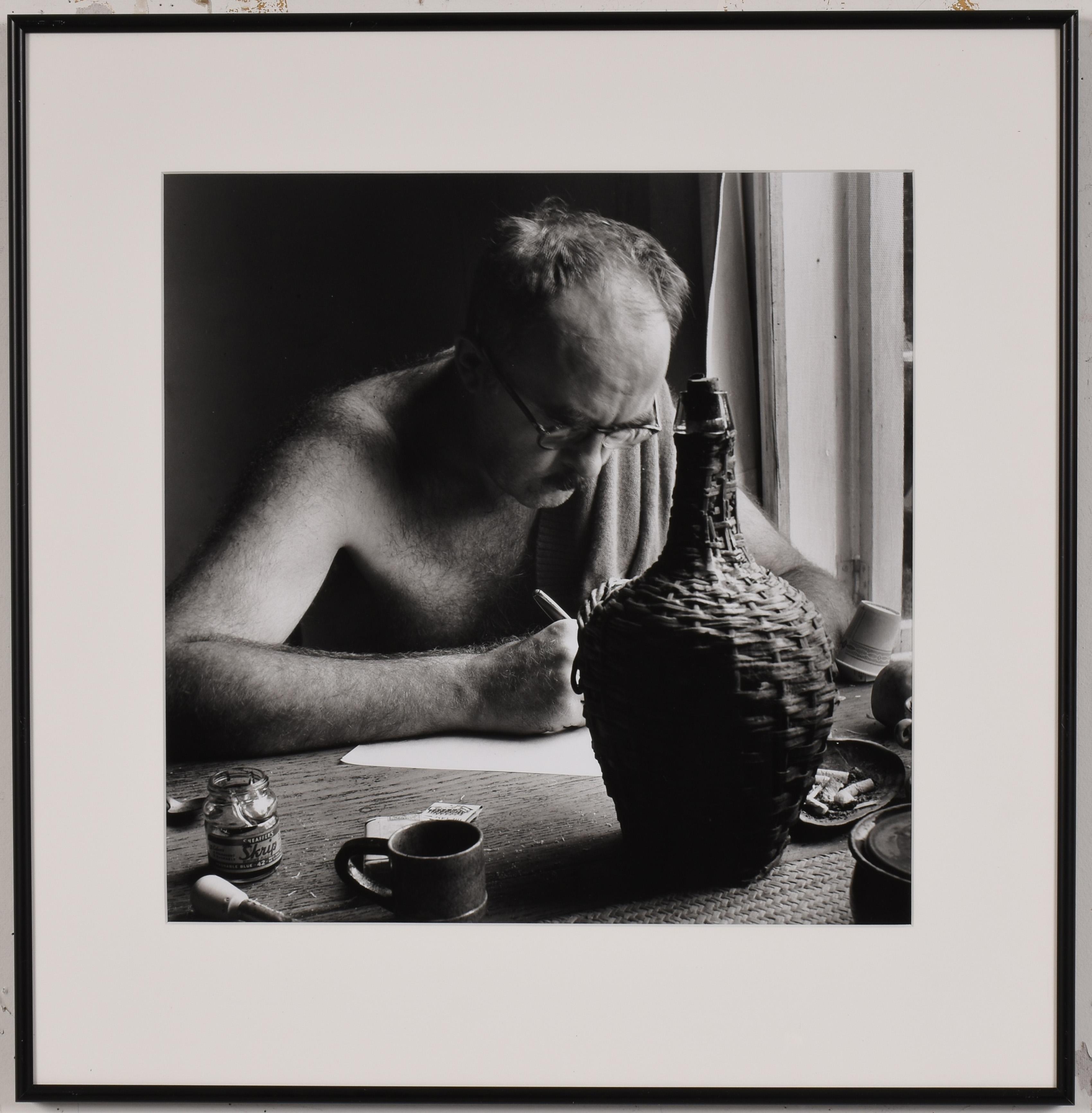

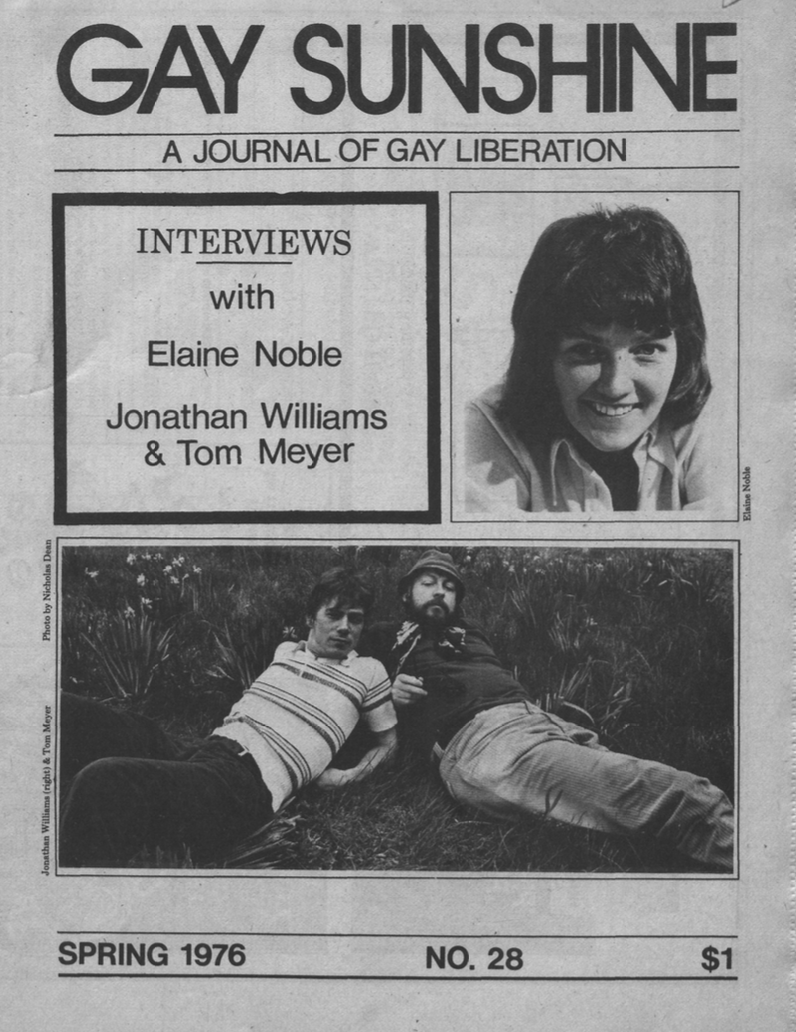

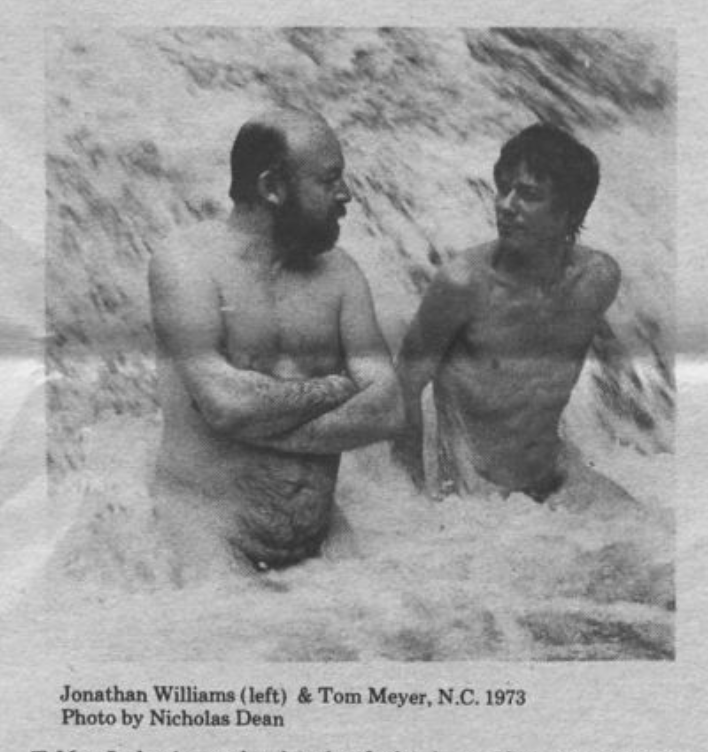

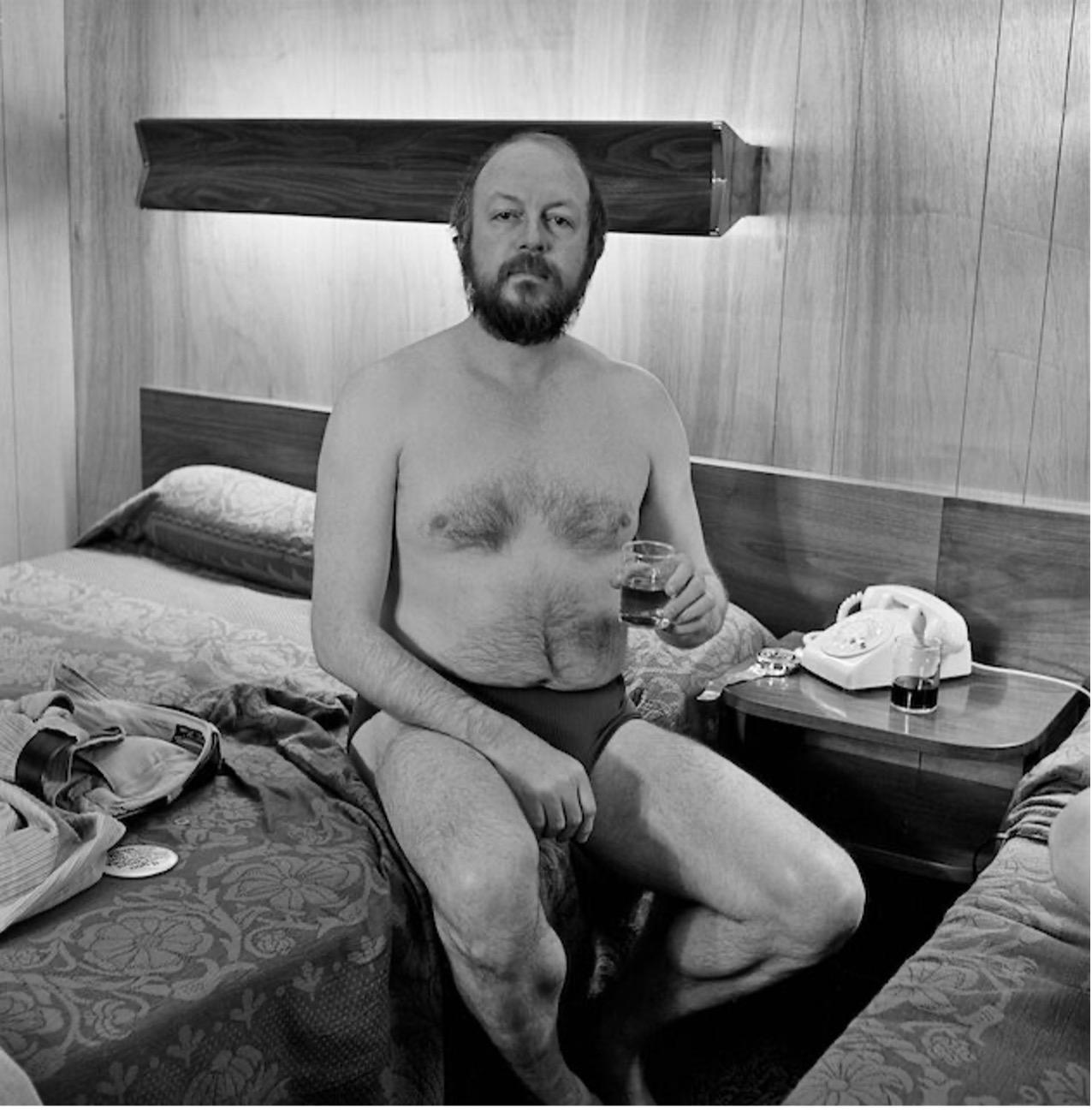

For the spring 1976 edition of Gay Sunshine: A Journal of Gay Liberation, Williams and Meyer posed for portraits by Nicholas Dean and Guy Mendes in settings that amplified rural charm (Figs. 19 and 20). Dean’s photographs depict Williams and Meyer within that desired pastoral landscape, laying in the flowers or swimming nude in a river. Mendes recounts a conversation he had with Williams on photography and memory during a shoot in a Best Western Motel for the magazine (Fig. 21):

I have just been telling Jonathan about archival processing of black & white photographs, about how, if properly handled, a black & white photograph will have a life of some 3,000 years (so the scientists say). When means they’re history [sic]. “Well, I suppose I should pull myself together.” Jonathan said and then sat to.[80]

Williams’s self-presentation to Mendes harkens back to the careful framing of his Black Mountain portraits, mostly black and white photographs. Like Williams, Mendes supplements the meaning of his portrait through colloquial conversation, adding a sense of dynamism to an otherwise static document. Within the post-Stonewall period, Williams shed light on his early homosexual experiences and thus resurrected the queer elements that percolate within his own photographic archive. The forum of Gay Sunshine permitted a change in context from which to view Williams’s BMC portraits and set a new narrative in motion.

Figure 19: Digital screenshot of the cover of Gay Sunshine: A Journal of Gay Liberation, Spring 1976. Photograph of Thomas Meyer and Jonathan Williams by Nicholas Dean.

Figure 20: Digital screenshot from Gay Sunshine, Spring 1976. Photograph by Nicholas Dean, 1973.

Figure 20: Guy Mendes, Jonathan Williams, Zoder’s Best Western, Gatlinburg, TN, 1974. From 40/40 – Forty Years Forty Portraits, 2010, published by Institute 193, Lexington, KY.

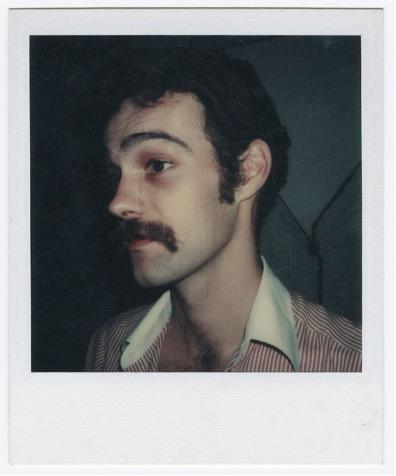

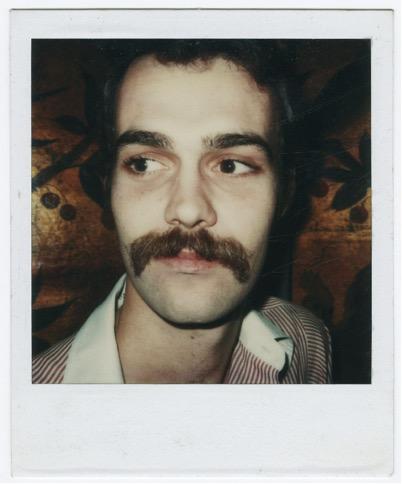

While being interviewed for Gay Sunshine in 1975, Jack Sharpless, a queer poet from San Francisco, asked Williams about the sexual atmosphere of Black Mountain, to which Williams replied “There was a lot of moonshine and a lot of homocidal foliage, as Edward Dahlberg called it—and a lot of healthy confusion.”[81] By this point, the myths of Black Mountain had circulated around the SF queer community, and Williams was viewed as a source of that material. Williams captured two closeup portraits of Sharpless on his Polaroid SX-70 sometime around the interview (Figs. 22 and 23). In each polaroid, Sharpless averts his gaze away from Williams, making it unclear of the one who voyeurs. In the posthumous publication of Sharpless poetry, published the year after he died from AIDS-related illnesses, Williams writes “Only a few times did I ever meet that huge, big-eyed cousin of the Pileated Woodpecker. That woody-woodpecker laugh. Amazing. Attractive. So alive.”[82] Another polaroid depicts Williams showing Sharpless a photograph (Fig. 24). Williams represents the queer collector, recalling one of his “meta-fours” poems on John Addington Symond’s collection:

excited by one of

baron von gloeden’s photographs

of a naked sicilian

shepherd boy he took

peeks during Robert browning’s

funeral service in westminster

abbey and john addington

symonds caught him red-handed [83]

Williams’s own photographic collection grew over the years, including prints by Callahan, Siskind, Wynn Bullock, Henry Holmes Smith, and Clarence John Laughlin, to name a few, as well as prints with homoerotic overtones, such as Lyle Bonge’s Dixie Bar of Music, Reuben Cox’s Nude of Tom Meyer Bathing in Middle Creek Falls, one of Joel Singer’s “Photages,” and Robert Doisneau’s Le Chant Du Départ.[84] From taking one’s portrait to showing them a photograph in his home or from afar through his publications, Williams understood the significance of incorporating queer photography within the lives of those he was most familiar.

Figures 22 and 23: Jonathan Williams, Jack Sharpless, ca. 1976-1978. Polaroid. Jonathan Williams Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Figure 24: Photographer unknown, Jack Sharpless and Jonathan Williams, ca. 1976-1978. Polaroid. Jonathan Williams Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

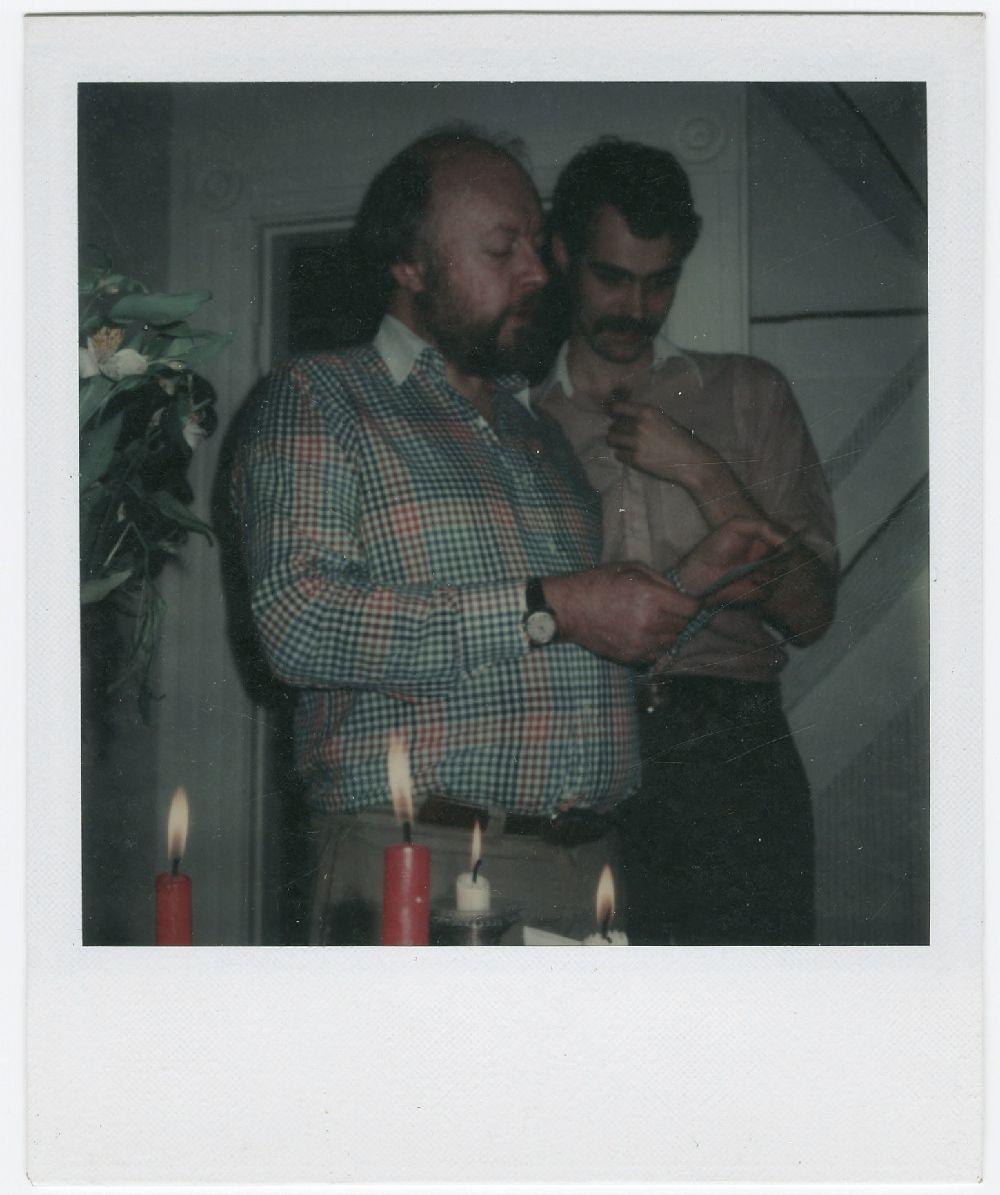

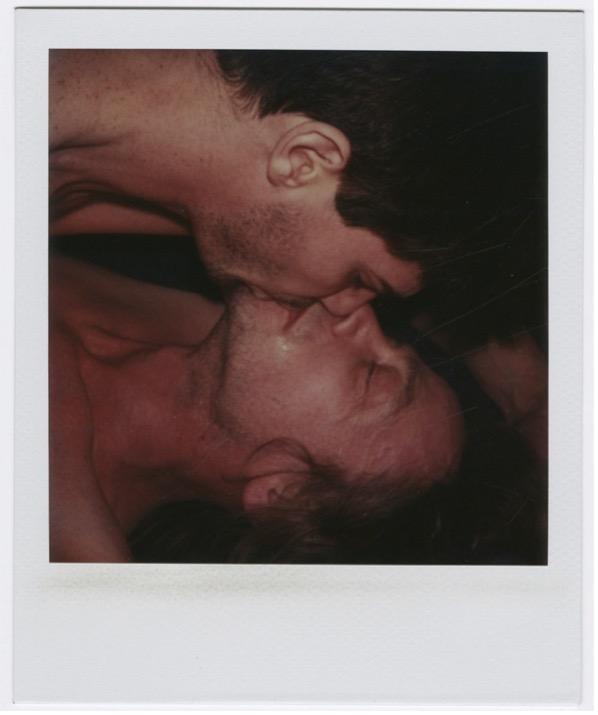

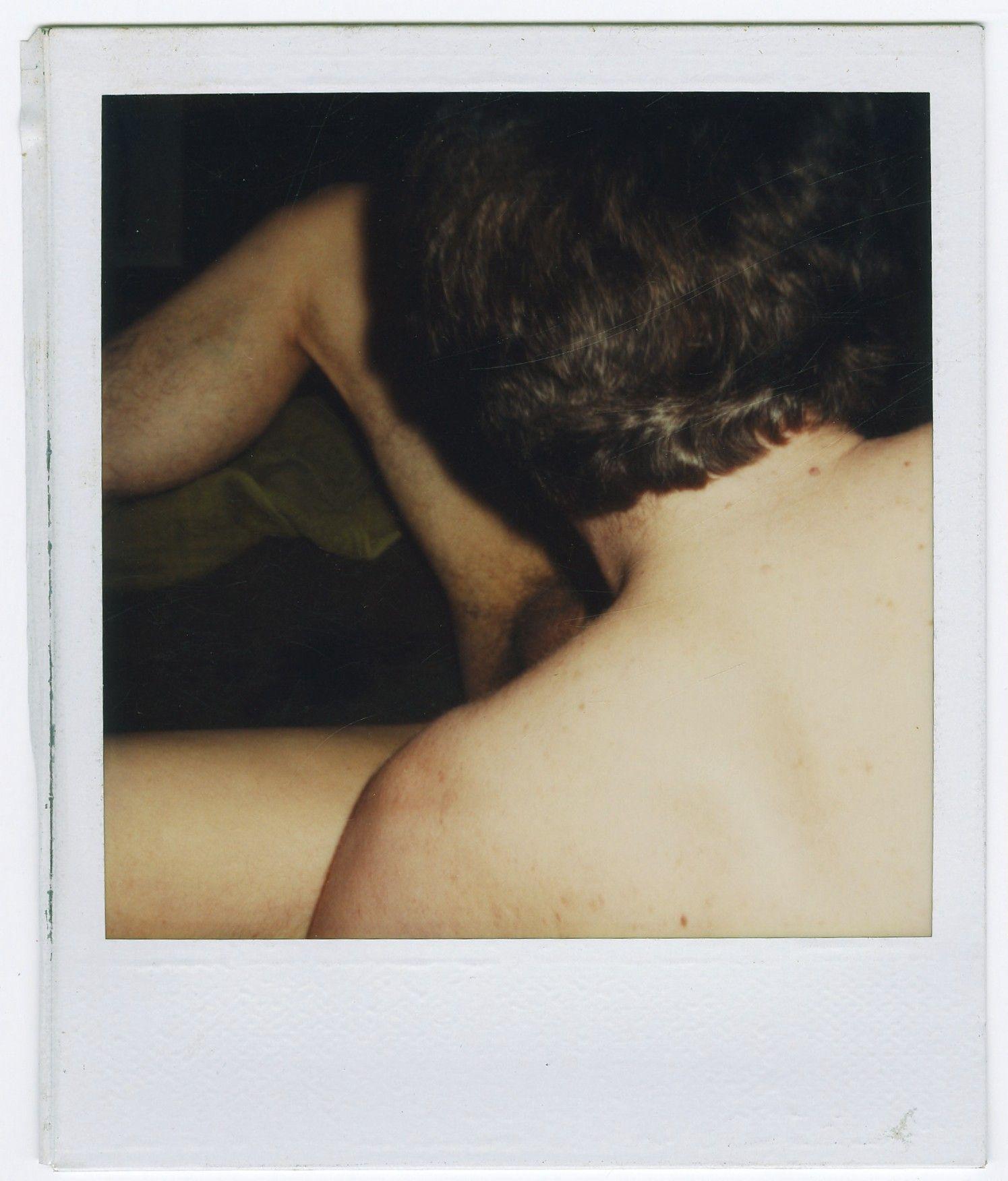

Williams’s archive takes a sharp turn into the pornographic when depicting the bodies of men captured on polaroid (Figs. 25-27). Either depicting his lover, Thomas Meyer, engaged in sexual acts with another male, or two, or the fragmented bodies of anonymous males, Williams was not averse to taking photographs that had explicit gay content. However, these images were never exhibited anywhere outside of Williams’s home,[85] and he did not publish them in his two photographic publications, Portrait Photographs and A Palpable Elysium. Williams did not have a darkroom, so producing polaroids ensured a sense of privacy as there was no need to send the images off for development. These polaroids could also not be readily reproduced, further ensuring they were meant for Williams’s eyes only, or for those who wanted to come visit and see them. When tracing the development of Williams’s queer vision from his early Rolleiflex portraits to his voyeuristic polaroids, we can’t help but wonder how radically different our conception of sexuality at Black Mountain would be if the SX-70 had existed back in the ‘50s.

Figure 25: Jonathan Williams, Thomas Meyer Kissing an Unidentified Man, 1976-1994. Polaroid. Jonathan Williams Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Figure 26: Jonathan Williams, Steven Teeter, Alden Ashford, and Thomas Meyer, ca. 1978-1995. Polaroid. Jonathan Williams Photographs. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Over the years, Williams engaged in numerous interviews on his experience at Black Mountain and circulated the work of his college peers, establishing their eminence within the communities he visited.[86] Williams actively engaged in the making of Black Mountain College’s collective memory, even volunteering to read an early draft of Duberman’s Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community, but he was also willing to show-and-tell the queer side of the story. In an introduction to an Aperture edition on Harry Callahan, Williams recollects on his time at Black Mountain: “Black Mountain was a place that gave you a real chance to find out who you were and what you could do. . . But, Black Mountain was also about important other matters: sex, friendship, music, poker, softball, learning how to drink, and learning how to talk.”[87] Williams’s Black Mountain portraits, often categorized as documentary evidence of the Black Mountain Poets, meant more to his circle than proof that they were at the College. For the queer poet and artist, Williams’s portraits tell a personal story that counters the institution’s governing history. They trace their inner moments of becoming, a metamorphosis that occurred at the cocoon that was Black Mountain.

[1] Williams was deployed to Stuttgart for 17 months after his first semester at Black Mountain College in the fall of 1951. He returned in the spring of 1954. He left BMC for San Francisco that fall in October and stayed for about 6 to 8 months, returned to BMC in 1955 and stayed until 1956. See Jonathan Williams interview with Martin Duberman, November 3, 1968, Martin Duberman Collection, Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina, pp. 9, 12, 29, and 32.

[2] See Martin Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (Northwestern University Press 1972 and 2009); Michael Rumaker, Black Mountain Days (Asheville: Black Mountain Press, 2003); and Fielding Dawson, The Black Mountain Book: A New Edition (North Carolina: Wesleyan College Press, 1991). Various accounts of homosexuality at Black Mountain can also be found in the Martin Duberman and Black Mountain College Research Project collections at the Western Regional Archives.

[3] See Interview with Duberman, p. 9. “It was the time of the McCarthy hearings. And so we’d go watch that on television.”

[4] Williams likely took more photographs at BMC than those that exist today within archives around the US, but due to years of projection many images have been destroyed. See the introduction of Jonathan Williams, Portrait Photographs (London: Coracle Press, 1979). “The older slides from the 1950s have been subjected to heat and light of a projector on hundreds of occasions and they have been dragged around the American continent inside a series of Volkswagens in all weathers. Brilliance has been lost and chemical breakdowns have had to be repaired.”

[5] Diana C. Stoll, “Jonathan Williams—More Mouth on that Man,” in Jonathan Williams: The Lord of Orchards, ed. Jeffrey Beam and Richard Owens (Westport and New York: Prospecta Press, 2017): p. 45.

[6] He wrote extensively on photographers, both well- and unknown, including but not limited to: Lyle Bongé, Clarence John Laughlin, Doris Ulmann, Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind, Wynn Bullock, Art Sinsabaugh, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, and Guy Mendes.

[7] Jonathan Williams, “The Camera Non-Obscura,” 1980-1981, in The Magpie’s Bagpipe: Selected Essays of Jonathan Williams, ed. Thomas Meyer (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1982): 85.

[8] Williams, “The Camera Non-Obscura,” p. 84.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid, p. 85.

[11] Richard Deming, “Portraying the Contemporary—The Photography of Jonathan Williams,” in Jonathan Williams: The Lord of Orchards, ed. Jeffrey Beam and Richard Owens (Westport and New York: Prospecta Press, 2017): p. 276.

[12] Deming, p. 275.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Deming, p. 272.

[15] Will Hamlin, unpublished memoir. Black Mountain Project Collection, Western Regional Archives, p. 6.

[16] Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community, pp. 230.

[17] Rumaker, p. 433.

[18] Rumaker, p. 219.

[19] Dawson, p. 113.

[20] See Student and Faculty Roster in Mary Emma Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2002): p. 267.

[21] Rumaker, pp. 29 and 85.

[22] Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community, pp. 348-349 and Harris, p. 169.

[23] Harris, p. 169.

[24] Jeffrey Beam, “Tales of a Jargonaunt: An Interview with Jonathan Williams,” Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2003, accessed January 2, 2023, https://www.raintaxi.com/tales-of-a-jargonaut-an-interview-with-jonathan-williams/.

[25] Interview with Duberman, p. 1.

[26] “Gay Sunshine,” Gay Sunshine: A Journal of Gay Liberation, Spring 1976. Archives of Sexuality and Gender accessed January 29, 2023, p. 3.

[27] Beam, np.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Harry Callahan Interview with Mary Emma Harris, March 16, 1971, Black Mountain College Research Project Collection, Western Regional Archives, p. 7.

[31] Interview with Duberman, p. 5. Ma Peak’s, a local bar, acted as an auxiliary classroom for students and faculty off campus.

[32] Beam, np.

[33] Interview with Duberman, p.12.

[34] “Jonathan Williams,” Prospect Into Breath: Interviews with North and South Writers, ed. Peterjon Skelt (Twickenham and Wakefield: North and South, 1991): 48.

[35] See Deming, 274. “ . . . William was clearly aware of how to make use of a photograph’s rhetoric to legitimate his avant-garde community.”

[36] Interview with Duberman, p. 13.

[37] This idea builds on Ross Hair’s essay, “’Hemi-Demi-Semi Barbaric Yawps’—Jonathan Williams and Black Mountain,” in which he points out Williams’s reference to Walt Whitman in his 1985 interview with Ronald Johnson as one of his numerous methods of disrupting Black Mountain’s masculine memory. “Williams’ allusion to Whitman subtly queers the heteronormative model of Black Mountain by identifying the homoerotic dynamics and tensions simmering under the surface of its intensely straight male bonds and heteronormative model.” See Ross Hair, “’Hemi-Demi-Semi Barbaric Yawps’—Jonathan Williams and Black Mountain,” Journal of Black Mountain College Studies 3 (2012), https://www.blackmountaincollege.org/volume3/3-2-ross-hair. Also published in Jonathan Williams: The Lord of Orchards, ed. Jeffrey Beam and Richard Owens (Westport and New York: Prospecta Press, 2017): p. 139.

[38] To read more about the role of gossip in the BMC archive, see Helen Molesworth, “Imaginary Landscape,” in Leap Before You Look, ed. Helen Molesworth and Ruth Erickson (New Haven and London: Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston and Yale University Press, 2015): 73.

[39] Gavin Butt, Between You and Me: Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948-1963 (Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2005): 12.

[40] A few other portraits by Williams of Gray are held in the Jargon Society Collection at the University at Buffalo Libraries. Two others exist from this shoot. See Box 609 Folder 42 and 44, PCMS-0019, The Jargon Society Collection, 1950-2008, The Poetry Collection, State University of New York at Buffalo.

[41] Francine du Plessix Gray, “Black Mountain: The Breaking (Making) of a Writer,” from Adam and Eve & The City, 1987, reprinted in Black Mountain College: Sprouted Seeds : An Anthology of Personal Accounts, ed. Mervin Lane (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1990): p. 306.

[42] Robert Dana, Against the Grain: Interviews with Maverick American Publishers, (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1986): p. 207.

[43] Barry Albert, “Jonathan Williams: An Interview (Washington, D.C., June 14, 1973),” VORT #4, Vol. 2 No.1 (Fall 1973): p. 66.

[44] “Gay Sunshine,” p. 4.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Jonathan Williams, A Palpable Elysium: Portraits of Genius and Solitude (Boston: David R. Godine, 2002): p. 118.

[49] Rumaker p. 490.

[50] Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community, p. 418.

[51] Jonathan Williams Correspondence, Martin Duberman Collection, Western Regional Archives.

[52] In a letter sent to Duberman, Williams notes that Figure 8 was “a rejected cover-photo for Creeley’s All That Is Lovely In Men.” Martin Duberman Collection, Western Regional Archives.

[53] Duberman brings up the split between Robert and Ann Creeley and his struggles at this point in his life in Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community, 417-421. See also Rumaker, p. 502.

[54] Rumaker, p. 494.

[55] Robert Creeley, All That is Lovely in Men : poems / Robert Creeley ; drawings / Dan Rice (Asheville: Biltmore Press, 1955): np.

[56] I dated this photograph to 1955 since Williams is wearing the same outfit in a photograph of him taken by Robert Creeley at BMC in 1955. See “Jonathan Williams: A Life in Pictures” in The Lord of Orchards.

[57] Rumaker recalls Williams’s sharp attire in his memoir: “ . . . in his Ivy League/Country Gentleman uniform of black corduroy jacket, expensive Abercrombie & Fitch hunter’s red wool shirt, black suede cap and chino trousers.” Black Mountain Days, p. 334.

[58] Du Plessix Gray, p. 306.

[59] Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community, p. 425.

[60] Williams Interview with Duberman, p. 52.

[61] Rumaker, Black Mountain Days, p. 181.

[62] Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community, pp. 139-140.

[63] Charles Olson & Robert Creeley: The Complete Correspondence Vol. 9, ed. Richard Blevins (Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1990): p. 62.

[64] Williams Interview with Duberman, pp. 37 and 38.

[65] University of Connecticut dates this photograph to 1953. Based on Fig. 13, I date it to 1955. Although this copy print was dated to ca. 1953, I believe that it was taken by Williams during 1955, as indicated by the date of Figure 13. Williams likely took the second set of portraits of Olson to announce the publication of Maximus Poems/11-22 (Jonathan Williams: Stuttgart, 1956).

[66] The most notable publication Dawson and Williams collaborated on was The Empire Finals at Verona (Jargon 30), published in 1959. Williams wrote the poems and Dawson created the collages and drawings.

[67] Fielding Dawson left Black Mountain in 1953, but this photograph was potentially taken by Williams during Dawson’s return visit in 1955.

[68] The Poetry Collection at the University of Buffalo acquired the print in 1991, when they purchased The Jargon Society Collection from Williams.

[69] Phone conversation with Thomas Meyer, January 13, 2023.

[70] Fielding Dawson, The Black Mountain Book: A New Edition (North Carolina: Wesleyan College Press, 1991): p. 12.

[71] Jonathan Williams: By Eye and By Ear, directed and edited by Monty Diamond, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H9mvY03A0U0&t=251s.

[72] Rumaker, p. 345.

[73] Rumaker, Black Mountain Days, p. 358.

[74] Rumaker, p. 538.

[75] “To the Committee on Graduation,” Rumaker to Olson, May 17, 1954, Olson Archives, Storrs, cited in Leverett T. Smith Jr., Eroticizing the Nation: Michael Rumaker’s Fiction, Black Mountain College Dossier No. 6 (Asheville: Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, 1999): p. 41.

[76] Letter from Jonathan Williams to Louis Zukofsky, March 4, 1958 (Washington, D.C.), Box 28 Folder 10, Louis Zukofsky Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

[77] Jonathan Williams: By Eye and By Ear.

[78] Williams, A Palpable Elysium, p. 50. To learn more on Duncan and Jess’ homelife, see Tara McDowell’s The Householders (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2019).

[79] Letter from Jonathan Williams to Jess (May 29, 1966), Box 68 Folder 23, Robert Duncan Collection, The Poetry Collection at the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

[80] Guy Mendes, “A Trip to Gatlinburg,” VORT #4, Vol. 2 No.1 (Fall 1973): p. 97.

[81] “Gay Sunshine,” p. 4. “Homocidal” is not an accidental misspelling here.

[82] Jonathan Williams, “What Could Be More Sharp,” in Presences of Mind: The Collected Books of Jack Sharpless ed. Ronald Johnson (Kentucky: Gnomon Press, 1989): p. 106.

[83] Jonathan Williams, Jubilant Thicket: New & Selected Poems (Port Townsend, Washington: Copper Canyon Press, 2005): p. 27. Also see James Downs, Introduction to A Carnal Medium: fin-de-siècle essays on the photographic nude (Portsmouth: Callum James Books, 2012: p. 25. “John Addington Symonds was an avid collector, travelling from his Swiss home to Taormina and Naples, where he once bought 96 photographs from Plüschow in a single visit. Some of these he passed on to Edmund Goose. Von Gloeden and Plüschow shared both model and props, which has resulted in frequent confusion in attributing authorship of images.”

[84] “Eye/Object: Photographs From the Collection of Jonathan Williams,” Stephen Daiter Gallery, accessed January 31, 2023, https://stephendaitergallery.com/exhibitions/eyeobject-photographs-from-the-collection-of-jonathan-williams/.

[85] E-mail correspondence with Thomas Meyer, January 18, 2023.

[86] Duberman, p. 439 and Hair, p. 161.

[87] Jonathan Williams, “A Callahan Chrestomathy,” in Harry Callahan: With an Essay by Jonathan Williams (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1999): p. 5.

Kyle Canter is a master’s student at Hunter College, where he is finishing his thesis on photography at Black Mountain College. He currently lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Cite this article

Canter, Kyle. “Jonathan Williams: Photography and The Queer Self at Black Mountain College.” Journal of Black Mountain College Studies 14 (2023). https://www.blackmountaincollege.org/journal/volume-14/canter