Why is the story of Peter Nemenyi important? The simplest answer is that Peter’s story adds a new perspective to our knowledge of Black Mountain College (BMC). The richness of the tale of BMC is in the history of the individuals who passed through this unique location. It is through the telling of their life stories—their struggles and conquests before arriving, their interactions at the College, and their accomplishments after leaving—that we learn of the significance of BMC. Every individual is important. Because of the College’s noteworthiness in art history, there are many books and articles about the art faculty and art students that attended BMC. There are very few investigations into non-art students at BMC. However, BMC was a liberal arts college with faculty and students in many other disciplines besides the arts. To have a full understanding of BMC, it is important to include stories of those individuals whose interests lie outside of the arts.

Peter Nemenyi was a science student who attended Black Mountain College for three years. He is one of the few students to complete all the requirements and to officially graduate. While a student, he worked with one of a handful of famous scientists who taught at the College.[1] Peter’s advisor was Max Dehn, a distinguished mathematician from Germany who was a faculty member at BMC for seven years.[2] Peter was able to use his experience at BMC to enroll in graduate school and continue his career as a scientist. After finishing at BMC, Peter went on to receive a PhD working in statistics at Princeton University. Like many of the students from BMC, Peter’s career leaned towards teaching and education. He worked at several colleges and universities where he taught and did statistical research and consulting. Peter’s story gives a perspective of BMC from a non-art student point of view. This is reason enough to investigate Peter’s life.

However, there is another valuable reason to tell this story. Peter’s story provides a microcosm of the turmoil and struggle that was unfolding around the world during his lifetime. At every stage of his life, Peter was dramatically impacted by world events. He is a Forest Gump type of character, showing up and witnessing firsthand the most important events of his lifetime. He was born in Berlin in 1927, the son of a Hungarian-Jewish family, putting his birth at the flash point of the chaos and war soon to overtake the world. He spent the war years as a child refugee in Europe separated from his parents. After coming to the US in 1945, and serving in the military, he attended BMC from 1947 to 1950. Attracted by the lure of studying with the mathematician, Max Dehn, Peter came to BMC to study mathematics and ended up in the middle of a modern revolution in the arts. After BMC, he began studying statistics and worked as an actuary in the New York City area. In 1963, he earned a PhD from Princeton University working with John Wilder Tukey, one of the most distinguished statisticians of the twentieth century.

Instead of continuing in industry, as an actuary or statistician, Peter turned his career towards education. During this period, he also became involved in the civil rights movement. He taught at two historically black colleges, worked in Mississippi on voter registration drives, and participated in marches and sit-ins. He was in Selma, Alabama, in 1965, days after John Lewis and others were beaten at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. He stayed and helped to organize as they prepared for the second march with Martin Luther King Jr. Peter’s life was tied up with significant events from the Cold War. He is probably the half-brother of the chess master Bobby Fischer. As the Reagan administration was caught up in the Iran-Contra scandal, from 1979-1983, Peter was working for the Sandinista government, in Nicaragua, as a statistician. Peter’s story gives a distinctive perspective of these important cultural events. Many of the issues Peter was deeply concerned about continue to disrupt our world today.

While many of the non-art students at Black Mountain College had outstanding careers, there are few, if any, that became as famous and attracted the attention of the media and historians as the art students. Because of this, it is difficult to find much documentation on any one non-art student. However, we are lucky when investigating Peter Nemenyi. We have multiple records. Of course, as a BMC student, we have Peter’s school records, which include his handwritten application, faculty evaluations, and letters of recommendation.[3] Peter himself kept records of his activities. He kept files on his employment, work with mathematical societies, and civil rights projects.[4] Near the end of his life, Peter was interviewed by a journalist collecting interviews with leaders in the civil rights movements of the 1960’s. The transcript of this interview provides, in Peter’s own words, many of the details of his life before and after BMC.[5] A few years after Peter’s death, reporters writing about the game of chess, investigated and published information on Peter’s family.[6] Together these resources provide a small view into the life of this unique individual.

Peter Bjorn Nemenyi was born on April 14, 1927, in Berlin, Germany, to Jewish-Hungarian parents.[7] His parents had fled from Hungary because of persecution by the antisemitic government. In Berlin they were members of a socialist group called the International Socialist Militant League (in German, Internationale Sozialistische Kampfbund (ISK)). The group held beliefs based on the philosophy of its founder Leonard Nelson. Besides comprehensive socialist political views, the ISK took ethical stands on issues such as animal rights. They followed a vegetarian diet and would not wear wool clothing. Before leaving Hungary, Peter’s father, Paul Nemenyi, studied in Budapest and was a physicist working on problems concerning fluid dynamics. After moving to Berlin, in 1922, Paul earned a Doctor of Science. He was a lecturer at the Technical University of Berlin when Peter was born.[8] At the age of three, Peter was sent to live at a small boarding school organized according to ISK ideology. He stayed with his parents on holidays and during the summer.[9] In the early 1930’s, the ISK members worked to unite several political parties against the rise of the Nazi Party. In 1933, when the Nazis came to power, ISK members were harassed. Because he was Jewish, Paul was forced out of his university position. On April 1, 1933, he was arrested by the SS and held for one day because of alleged statements he had made against Hitler’s government. Because of the lack of evidence, he was released.[10] In 1934, when Peter was seven, his parents separated and both fled from Germany. His mother went to Paris while Peter and his father went to Denmark with other families associated with the ISK.

In 1933, the Nazis closed the ISK school. However, a smaller version of the school, with two teachers and eight students, restarted the following year in Denmark.[11] The families lived on land that had been redistributed from landholdings of the nobility. The school was in an old castle. There was no plumbing so water needed to be brought up cobblestone steps every day. The students and teachers grew their own food in large gardens and did what they could to keep the school going. Classes included touring around Denmark on bicycles while sleeping in barns along the way. In the 2000 interview, Peter recounts that he received a “socialist education.”[12] He mentions that on one classroom door was a large picture of Paul Robeson, an African-American musician and political activist, with the words (translated into German) “I don’t hate you my white brother, I don’t hate you but why do you bully me?” Peter attributes this education to his motivation to work with civil-rights groups in the 1960’s.

World War II had a profound effect on Peter’s early life. In 1938, with help from the Quakers, the ISK school moved to Wales. That year, Peter’s father, Paul, moved to the US with hopes of finding a job. Peter was left to stay at the ISK school. During this time, he would visit his mother, who by then was living in London. However, in 1939 as Peter notes in his BMC school records, his mother died, and he was left alone in Europe without parents.

As soon as he arrived in the US, Peter’s father, Paul Nemenyi, began searching for employment. He visited Albert Einstein, in Princeton, and sent his vita to the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars. Probably because of his socialist background, the committee found him to be an undesirable person. However, Paul was able to find a position doing hydraulic research with Einstein’s son at the University of Iowa. In 1941, Paul began a position as an instructor at the Colorado State College in Fort Collins. In 1944, Paul moved to take a new position at the State College of Washington (now called Washington State University in Pullman). He stayed there until 1947. During this time, he was also doing classified government work in Hanford, Washington, with the Manhattan Project.[13]

Meanwhile, Peter had been unable to reunite with his father. In 1940, a teacher from the ISK school arranged for Peter to sail on a ship carrying refugee children to Canada. However, shortly before the voyage was scheduled to leave, a U-boat sunk the SS City of Benares, a similar ship transporting refugee children, and Peter’s voyage was cancelled. Peter spent the war years in Wales and England, living with Quaker families and at homes for refugee children. Not until the end of the war was he able to board a ship and sail across the Atlantic to be with his father.[14]

In 1945, Peter was able to get one of the first civilian passages to the US, sailing from Greenock, Scotland, to Halifax, Canada. After spending some time in New York City with people from the ISK, he took a train across the country to meet his father in Spokane, Washington. Peter enrolled at the State College of Washington, where his father was a professor. Peter completed a few classes before learning that he had been drafted. His father suggested he might consider going to Canada to avoid the draft. However, Peter chose to serve. The war was over and after his service he planned to use the GI Bill to attend college. Peter did basic training at Fort Lewis and was then stationed for nine months in Northern Italy, outside Trieste.[15]

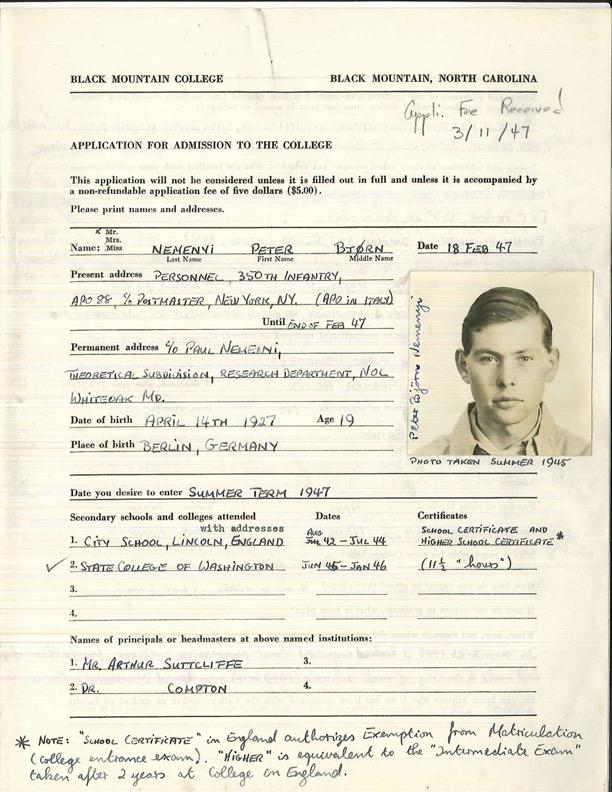

Figure 1. The first page of Peter Nemenyi’s BMC application. Courtesy Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina.

When Peter returned, it was his father who suggested he look at progressive colleges and gave Peter a list of schools to consider. Peter was released from his military duties on the East Coast and given five cents a mile to travel home. Since his address at the time was in Washington State, he was given a large sum for travel. However, by that time his father was living in Washington, DC. In 1947, Paul had been appointed as a physicist with the Naval Ordinance Laboratory in White Oak, Maryland. Peter used the money to take a trip around the country to see the sights and visit colleges. He went through the South to Southern California, up the coast to Northern California, and back through Chicago, stopping at several places along the way, including visits to both Antioch and Oberlin College. In the end, Peter chose to attend BMC because “it was the kind of progressive place … that was kind of most like home.”[16] He was also impressed that already in 1947, BMC was desegregated.

Peter was a student at Black Mountain College from the summer session of 1947 to the Spring of 1950. He took a leave from BMC for the 1948-49 academic year to follow his advisor, Max Dehn. Both went to the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where Professor Dehn had a visiting position. Peter is one of the few BMC students to finish and graduate. Many of Peter’s classes were with Max Dehn, including classes in calculus, projective geometry, advanced mathematics, descriptive geometry, complex variables, differential equations, advanced algebra, as well as philosophy and ethics. Peter also enrolled in music courses. His college records show that several semesters he attended a class in both chorus and piano. He enrolled in several courses taught by Charlotte Schlesinger, who was a famous classical musician from Berlin. Peter attended two of the summer sessions. In the summer of 1947, he took an Italian class, piano lessons, and a mathematics course from Professor Dehn. Peter also attended the famous 1948 summer session.[17] This was the first summer that John Cage and Merce Cunningham attended. Last minute changes to the faculty made room for Buckminster Fuller to teach architecture and Willem de Kooning to teach painting. That summer, Peter took Design with Josef Albers and Beethoven Sonatas with Erwin Bodky, a distinguished concert harpsichordist. One semester Peter led a group of students who convinced the campus to have a weekly “Mush Day.” On this day meals were made of simple food and the money saved was sent to families in Europe who were in need.[18] He did his graduation thesis on gamma functions. His outside examiner was Emil Artin, who at that time was a professor in the Mathematics Department at Princeton.

Figure 2. Peter Nemenyi (front seat center) on his way to Asheville for a “Song Festival” with MC Richards, Nicolas Muzenic (front seat), and Ted Dreier Jr. (back seat). c. 1948. Courtesy Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina.

After Black Mountain College, from 1950 to 1952, Peter went to graduate school in mathematics at Princeton University. On March 1, 1952, Peter’s father unexpectedly died of a heart attack at the age of 56. Only a few months later, on June 27, Peter’s BMC advisor Max Dehn also passed away. Peter did not finish his work on a graduate degree at this time. Instead, by 1953 he had moved to New York City and was shuffling between several temporary jobs. For a time, he worked at the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in the actuarial department. By the mid 1950’s he had found a temporary assistant professor position teaching statistics to medical students at the Downstate Medical College in Brooklyn.[19] [20]

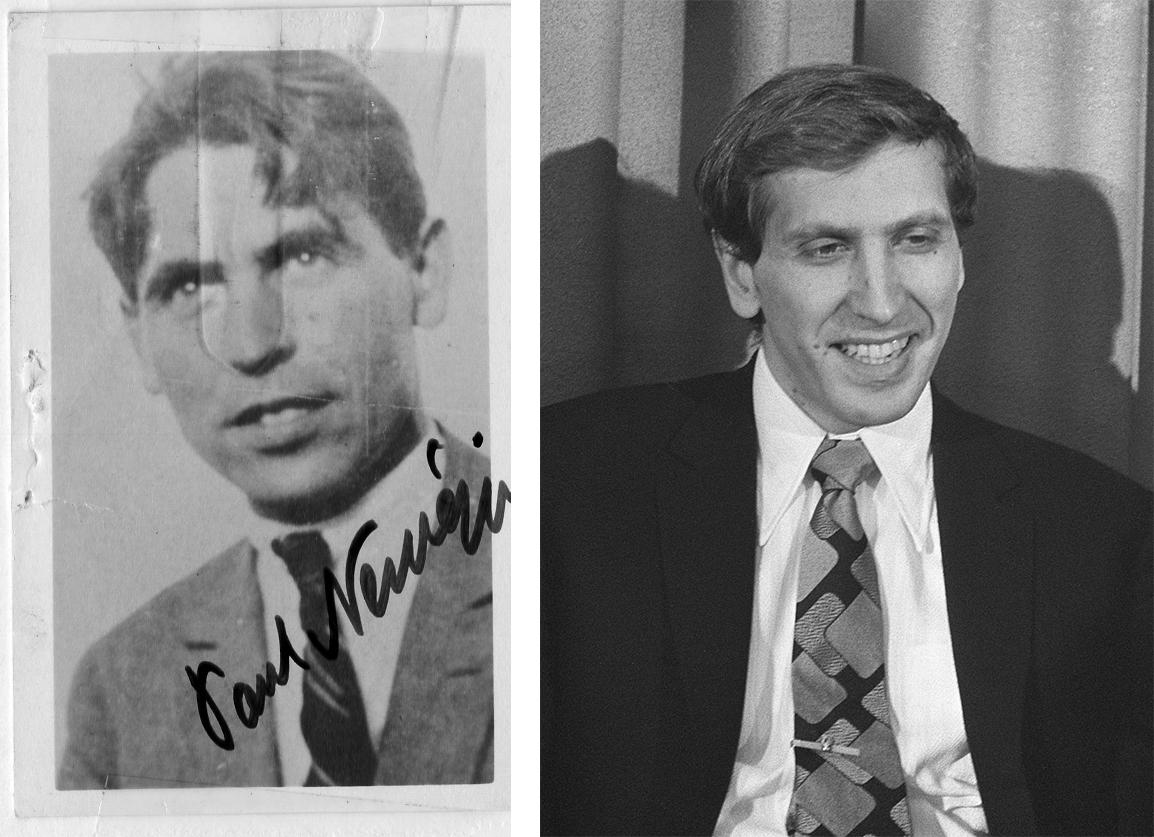

In 2002, fifty years after his father’s death and the same year that Peter Nemenyi died, a husband-wife team of journalists, Peter Nicholas and Clea Benson from the Philadelphia Inquirer, began an investigation into the famous chess master Bobby Fischer. Even though Bobby and his mother had always indicated otherwise, these journalists believed that Bobby Fischer’s father was Paul Nemenyi. Bobby Fischer had attracted the world’s attention in 1972, when he won the World Chess Championship, defeating the defending champion, Boris Spassky from the Soviet Union. Fischer immediately became a hero in the United States, appearing on magazine covers and television talk shows. However, for the next two decades he refused to play in chess tournaments. He became a sort of recluse occasionally appearing in public to talk of conspiracy theories and to declare his antisemite views.

The journalists were particularly interested in learning more about the man reported to be Bobby’s father, Gerhardt Fischer. As part of their investigation, under the Freedom of Information Act, they requested the FBI files on Regina Fischer. In 1942, after someone reported seeing suspicious papers in her home, the FBI became interested in Regina and began a file on her. When her son became a world chess champion, the FBI continued updating this file. To the journalists’ surprise, the files indicated that the FBI did not believe that Gerhardt Fischer was Bobby’s father. In fact, the FBI suspected that Paul Nemenyi was Bobby’s father. In 1942, Paul met Regina while she was a student in Denver, Colorado. Bobby Fischer was born in Chicago, March 9, 1943. The files indicate that the FBI believed that Regina had been in the US since 1939 however Gerhardt had never entered the country. The FBI files also noted that Paul Nemenyi had been sending Regina child support and had indicated to social workers that he had concerns about her care for Bobby.[21]

This insight from the FBI files led the journalist team to Peter’s papers on file at the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison. Peter Nemenyi’s papers include letters from shortly after his father’s death in 1952. In one letter, Regina Fischer wrote to Peter stating that Bobby had been sick and that she could not afford a doctor or medicine. Regina goes on, “I don’t think Paul would have wanted to leave Bobby this way and would ask you most urgently to let me know if Paul left anything for Bobby.”[22] Regina also asked that Peter inform Bobby of Paul Nemenyi’s death. Apparently, Peter had only met Bobby a few times and was uncomfortable with the request. Peter wrote to Bobby’s psychiatrist for advice and in the letter Peter states, “I take it you know that Paul was Bobby Fischer’s father.”[23] In public statements, Bobby Fischer seemed to believe that Gerhardt Fischer was his father. Regina Fischer also insisted that Gerhardt Fischer was Bobby’s father. There is still some disagreement in the chess community over this issue. However, it is very possible that Paul Nemenyi was Bobby’s father and therefore, Peter Nemenyi was Bobby Fischer’s half-brother. This is clearly what Peter believed.

Figure 3. Photo of Paul Felix Nemenyi. (Sent to Theodore Von Karman in1943 as part of a letter inquiring about a teaching position at Caltech). Caltech Images Collection, scan courtesy of the Caltech Archives.

Figure 4. Bert Verhoeff / Anefo (photographer), Bobby Fischer in Hilton Hotel in Amsterdam, 31 January 1972. Photo accessed through Wikimedia Commons, CC 1.0 courtesy of the Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Fotocollectie Anefo.

Peter’s significant work in mathematics and statistics began soon after college. In 1952, two years after Peter finished at Black Mountain College, Chelsea Publishing released an English translation of a famous book by David Hilbert and S. Cohn-Vossen, with the English title Geometry and the Imagination.[24] It is likely that Peter was the translator for his book. The book expands on material from a class Hilbert taught in Göttingen during the winter of 1920-21. In the preface, Hilbert states that the purpose of the book is to present geometry “in its visual, intuitive aspects.” Hilbert’s book was not for the mathematical expert, instead it was for “anyone who wishes to study and appreciate the results of research in geometry.” It included, without rigorous proof, topics such as, projective configurations, differential geometry, and topology. It seems clear that Max Dehn used the German edition of this text as a basis for his famous Geometry for Artists class at BMC. Notes from Ruth Asawa, another BMC student, show that many of the topics from the text were covered in Dehn’s class.[25] Dehn had been a student of Hilbert’s when Hilbert was doing some of his most important work in Geometry. Dehn himself had done research and solved fundamental problems associated with topic areas included in the book. Now teaching at a liberal arts college, Dehn clearly saw the importance of this unique book by his advisor. It is likely that Dehn encouraged Peter to translate this book into English. The front page of the text indicates only that it was translated by P. Nemenyi. Reviewers have interpreted this as Paul Nemenyi, but this is unlikely. At the time Paul was working as a physicist at the Naval Ordinance Laboratory and his interests were in fluid dynamics. He would likely not have had time or interest for this type of project. On the other hand, Peter had probably spent a few years tutoring other BMC students who were trying to understand Dehn’s class on this material. In a 2013 MAA Review of the 1999 edition, Tim Penttila (who attributes the translation to Paul) stated that, “It is beautifully written and carefully translated.” He ends the review with, “In summary, this book is a masterpiece—a delightful classic that should never go out of print.”[26]

Chelsea Publishing Company was a New York City-based publisher committed to republishing and translating important European mathematical books that were not available in the United States. After the founder’s death, the company was acquired by the American Mathematical Society (AMS). Inquiries to the AMS have not produced records to definitively determine which P. Nemenyi was the true translator. However, there is further evidence to support Peter’s case in Peter’s files at the Wisconsin Historical Society.[27] In a letter from Regina Fischer to Peter, dated March 30, 1952, Regina asks Peter if he has information about translation or typing jobs she could do at home. Regina notes, “Paul mentioned you were doing some translation of a book at home.” In his reply to Regina, from April 5, 1952, Peter provides the following information. “The only lead I can give you on translation work is to contact Mr. Galuten of Chelsea Publishing Company … I did my translation for him, …” There is also evidence that Peter began to do another translation for Chelsea Publishing Company years later, in 1965. In Peter’s files there are three letters on Chelsea Publishing Company letterhead indicating that Peter was paid $1,850 to begin translating A Textbook of Topology, by Seifert and Threlfall. However, Peter and the editor seemed to have had trouble working out how close Peter’s translation should stay to the original text. The letters indicate that, while the editor wanted Peter to continue, Peter wanted to return the money and stop working on the project. This seems to have been what happened. The text was translated by a different publishing company in 1980.

By the early 1960’s Peter had returned to his work at Princeton. In 1963, he received a PhD working with the renowned statistician John Wilder Tukey. Peter’s dissertation, Distribution-Free Multiple Comparisons, included a test that is still an important statistical tool used today.

During this time Peter became more involved in political activity. He joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He helped to campaign for Ed Koch, who Peter said was progressive at the time. By 1960 he had become interested in the civil rights movement happening in the US. He participated in some of the earliest New York CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) projects, including sit-ins, all-night vigils at the governor’s residence, and voter registration drives in Harlem. He had heard about the sit-ins that SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) was organizing in Greensboro, NC, and other places in the South. In 1962, when he had a couple of weeks of vacation, Peter decided to visit the SNCC office in Atlanta where they were working on the Voter Education Project to register and mobilize black voters in the Deep South. There he met Julian Bond, who asked him to go to Jackson, Mississippi, and help Joan Trumpauer, a white activist who had served jail time for her work with the Freedom Riders. He met Dorie Ladner, Bob Moses, Medgar Evers, and others involved in the civil rights movement in Mississippi. Peter assisted with the voter registration project. However, he notes that he was not sent to do work in the county, or any dangerous assignments, where a naive young white activist many have sparked trouble. In order to help understand the demographics of the population, Peter decided to get information from the Mississippi Department of Education. As it turned out, the Department of Education had not anticipated that a professional statistician would be helping the SNCC organizers. The Annual Reports contained a wealth of information, including details that showed the inequity of Department funding between programs for white students and programs for black students. Peter’s statistics were used by SNCC organizers and their lawyers.[28]

While working in New York, Peter continued to travel to Jackson to help with SNCC programs. In 1963, he attended the funeral, and associated protests, for his friend and civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who had been assassinated by a member of a white supremacist group. On one trip to Jackson, Peter visited Tougaloo College with Joan Trumpauer, who was a student at the college. She was the first white woman to be a student at this historically black college. Her enrollment created conflicts with her family, as well as national groups such as the KKK. The next year, 1963-64, Peter applied for and was given a position teaching mathematics and statistics at Tougaloo College in Jackson and continued his work with SNCC.[29]

That summer, the “Freedom Summer,” Peter did not stay in Mississippi. Before he realized what would be happening that summer with SNCC in Mississippi, he had taken a position teaching mathematics in a summer program at Oberlin College. Indecision over job offers, including an offer to return to Tougaloo, left him without a job for the 1964-65 academic year. Instead of teaching, Peter moved to Laurel, Mississippi, and devoted himself full-time to the SNCC efforts. In Laurel, Peter joined with other activists working for the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), an umbrella organization devoted to voter education, that included CORE, NAACP, and SNCC members.[30]

In Laurel, Peter worked on voter registration, testified at Civil Rights Commission hearings, and helped to prepare for the Freedom Democratic Party efforts taking place in the state. In March of 1965, days after the brutal beating of John Lewis and others as they tried to march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Peter joined many of his fellow SNCC members in Selma, Alabama. He helped to organize as the group prepared for another march, from Selma to Montgomery. The march was delayed as leaders negotiated to get President Johnson’s guarantee of federal protection for the marchers. Peter states that he spent a lot of time “in front of the police cordon and singing songs.”[31] He also had time to meet and talk with several SNCC and SCLC leaders, including James Bevel. He participated, on March 21, along with Martin Luther King Jr. and thousands of other people, as the group started their hike out of Selma. It was planned that only of small number, about 300 people, would do the entire four-day trip. Peter later admitted that though he had regrets, he was happy that he had not been picked for the tough hike. He would not have been prepared for the hardship of the 58-mile journey. Peter joined the marchers for the last day’s journey into Montgomery. The following day, March 25, he assembled with tens of thousands of people at the state capital and heard Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his speech, “How Long, Not Long.”

Peter’s files contain several detailed accounts of violence against him and other COFO members during his year working in Laurel, Mississippi. Included in the files is a two-page typed document from November 3, 1964. It appears to be his official statement to two FBI agents providing a detailed account of being beaten while he was doing volunteer work for COFO near a polling station in Laurel. There is another file detailing Peter’s arrest on December 23, 1964, and subsequent three-day stay in jail, after he went with a racially mixed group to try to order food at a local Travel Inn Coffee Shop. There is a two-page document titled, “Incident Report—Burning of the Laurel COFO Office,” that provides an account of damage from a fire in February, of 1965. The report notes that a few weeks earlier the office had received several threatening phone calls and a gunshot had been fired into the building. Another report titled “Bombing of the COFO Office, Laurel, Miss,” provides details of the fire-bombing of the new COFO office the following July. Peter notes that, “The building was not too badly damaged, primarily because it had been insulated with fire resistant sheet rock just before COFO rented it …” This had been done because the former Laurel COFO office had been burned.[32]

After a year in Laurel, Peter had a string of academic positions teaching mathematics and statistics. For a year and a half, he worked at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Then for six years he taught at Virginia State College, in Petersburg. For a short time, he had a visiting position at the University of Maryland, at College Park. Later he worked at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, assisting in statistics labs, helping faculty with statistical analysis, and planning research projects.[33]

There are several instances where Peter’s strongly held values brought him up against college and university administrators. He was a member of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and a staunch supporter of that organization’s commitment to academic freedom and education’s contribution to the common good. His own upbringing and education had left him with little tolerance for authoritarian tendencies in bureaucratic organizations. At every academic institution where he worked, there are records in Peter’s files of letters to presidents and other administrators critiquing their actions. He advised and worked with teaching assistant unions in their struggles with campus administrations. He supported faculty whose contracts were not renewed. He wrote letters to editors of school and local newspapers outlining his concerns. He involved the local AUPP and other organizations. At every chance, Peter would raise his voice to support anyone he felt was being persecuted by an unjust system.[34]

Even during Peter’s time at Virginia State College, a public historically black college which would seem a great fit for Peter, he had trouble when he felt the administration was acting unjustly. At VSC, Peter was the Head of the Statistics Department. He was the only full-time faculty in the department. He coordinated with part-time faculty across the campus to provide “undergraduate instruction, graduate instruction, and consulting service.” An evaluation of Peter’s work from April 5, 1971, by the Director of the School of Arts and Sciences, states that “Dr. Nemenyi has discharged the duties of Chairman of the Statistics Department in a manner which reflects a great concern on his part for effective and meaningful course experiences in statistics.”[35] However, the evaluation goes on to say, “His concern to improve teaching conditions in the Department has possibly resulted in his following procedures which are not consistent with College policy.” The evaluation concludes on a positive note, “Although Dr. Nemenyi indicated that he did not desire an increase in salary, his effectiveness as a teacher and his concern for his students certainly would justify a merit increase.”[36]

Peter kept several documents, from his time at VSC, that illustrate how bullheaded he could be when dealing with administrators and authority figures. For example, in 1970, Peter became embroiled in a controversy between a group of students and the President of the College. Peter’s files contain a four-page typed letter he wrote to the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) dated September 21, 1970. The letter provides a detailed account of what he clearly saw as the persecution of these students by the College President.[37] Eventually an American Civil Liberties Union lawyer was brought in to help the students. The case was brought to District Court. In Peter’s files there is a copy of an article he wrote that was published in the student newspaper. The article provides a detailed account of what Peter saw as the unfair way the college had treated the students and includes a scathing evaluation of the College President’s actions. The next academic year, Peter’s files show that he again was having troubles with the College President. These papers, and several others in his files, illustrate how far Peter was willing to go when he felt that someone had been unjustly treated by a person in power.

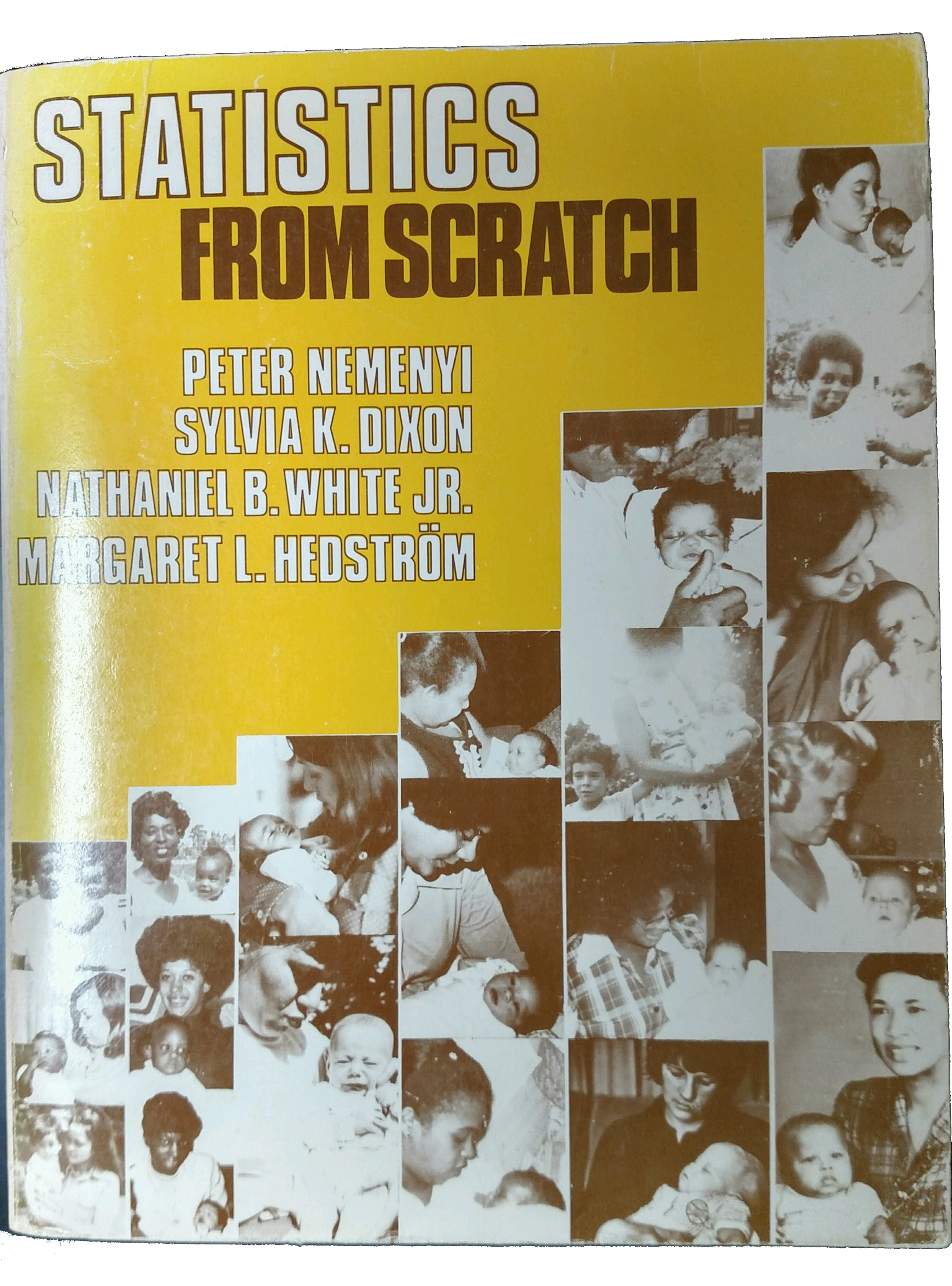

Figure 5. Statistics from Scratch by Peter Nemenyi, Sylvia K. Dixon, Nathaniel B. White Jr., and Margaret L. Hedström. Photo of the book’s front cover courtesy of David Peifer.

Throughout his career, Peter worked to promote a deeper understanding of statistics for everyone. He felt that education in statistics and basic computer operations was important. He saw these skills as essential for creating better informed citizens and to help those citizens prepare for future careers. Peter was the first author for the textbook Statistics From Scratch, published in 1977.[38] This book provides an introduction to statistics while requiring very little mathematics background. The preface suggests that it would be suitable for students in “social sciences, education and biological sciences…” In many ways this book was ahead of its time. It is filled with real applications taken from scientific articles and provides informal, yet in depth, explanations of the statistics used. Early on the authors advise that a computer would be helpful for many of the problems with larger data sets. Computer programs in BASIC are supplied throughout the book. The writing is informal and even enticing as the reader is guided though questions that must be considered in each study. Many of the data sets come from medical studies on public health issues.

Peter’s socialist tendencies are evident throughout the text. In the first chapter there are examples that include studies of salaries in states with “Right to Work Laws.” These laws hamper union efforts to organize and recruit members. In the book, Peter notes that, “The word Statistics was first used in the 17th century to refer to bodies of information about the state (state-istics).”[39] The text does not shy away from political topics, such as a detailed investigation of a study from 1972 by Anthony Russo, whom the book notes the Nixon administration had tried to convict for letting out information on the Vietnam War. The study considers several provinces in Vietnam. Information was available on what percentage of each province was under Saigon control versus Viet Cong control. The study investigated the level of five specific economic and social characteristics as compared with the percentage of Saigon control to determine if there was a relationship. Russo’s conclusion was that Saigon would have a better chance of controlling an area if it improved the economic wellbeing of the peasants. Another study, favored by the Nixon administration, came up with exactly the opposite conclusion. Peter points out that it is hard to find truth through statistics. He states,

“As a citizen I support Russo’s position… As a statistician or objective observer I cannot formulate a definite conclusion, a sure specific interpretation, until I’ve gone over multivariate analyses of many variables thoroughly, examined many different authors’ positions, and considered all the available historical information; in other words, never. A rational course of action must be something in between, where we evaluate our present knowledge and information to the best of our ability and act on it, while keeping our minds open to further information which may change our views later.”[40]

On December 31, 1977, Peter was among a group of eleven statisticians who wrote Jerome Cornfield, the President of the American Statistical Association (ASA).[41] The group was “interested in promoting efforts on behalf of minorities in statistics.” The letter includes proposed resolutions to be considered by the association. The suggested resolutions begin with, “to increase significantly the representation of minority groups both in the profession and in the Association.” They go on to suggest that the ASA, “Develop specific proposals and find financial resources for the recruitment and training of minority statisticians” and request the establishment of an ASA Standing Committee on Minorities in Statistics. In a letter from January 24, 1974, Cornfield responds that he is appointing an ASA Ad Hoc Committee on Minorities in Statistics, which includes Peter as a member and would be chaired by Charles Bell of Tulane University. In a meeting that February, the committee discussed, among other items, focusing attention on students at the BA level and modifying the “Careers in Statistics” brochure.

It appears that Peter had more thorough modifications in mind than other members of the committee. In a letter from May 15, 1977, Peter states the case for his version of the brochure. He suggests a “more lively” presentation and states,

“I think examples should be used, to make the role of statistics come alive. And it seems absolutely preposterous to me to insist that this brochure should not be `political’ … Why should we not quote statistics of the state we live in? If it’s a racist state (as we know it is), why should we ende[a]vor to hide this fact? … Most particularly as a committee concerned with equal opportunity in the profession in America, why would we shy away from statistics of unequal opportunity in America? And why shouldn’t it interest students who are subject to the racist society to learn that statistics can be a tool to understand and deal with society?”[42]

During the summer of 1979, Peter had a chance to visit friends in South America. He had a friend living in El Salvador doing a dissertation on mosquitos and a former student of his living in Costa Rica. While in El Salvador, Peter visited the University of San Salvador where he heard Archbishop Romero and others speak at a program organized by the law school. While traveling to Costa Rica he passed through Nicaragua and decided to visit the Mathematics Department at the University of Nicaragua. At this time Nicaragua was in the middle of a socialist revolution. The Sandinista National Liberation Front (in Spanish, the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional) were fighting to overthrow the dictator Anastasio Somoza DeBayle. According to Peter, the faculty he met at the university were “very much involved in the movement.”[43] (Michaels 2000) By mid-July that year, Somoza was forced to flee the country and the Sandinistas took control of the government. Peter quickly went to the new Sandinistas Embassy in Costa Rica and got a visa to enter Nicaragua. He was offered a teaching position at the university but felt uncomfortable with his Spanish language skills. Within a few months he was given a position working for the government as a statistician. First, he worked in the Sandinistas’ version of a census bureau and later in the research office of the ministry of agriculture and agrarian reform. Peter stayed in Nicaragua for three and a half years until he became very ill.

Peter developed severe problems with his stomach and intestines. He had three operations at Manolo Morales Hospital in Managua, El Salvador. However, the hospital could not handle his condition. Some of Peter’s friends convinced the people at the American embassy that it would be bad publicity to let an American citizen die in El Salvador, so the embassy found funds to pay for an ambulance plane to fly Peter and his doctor to a hospital in Miami, where Peter had several more operations.[44] At this time Peter moved to Durham, North Carolina. Peter had very poor health for the rest of his life and went on disability. In the interview from 2000, Peter states that he continued to do volunteer work with the Witness for Peace program and “a little bit here in statistics, math and that.”

Peter died in 2002 in Durham, NC. An obituary in The Raleigh, NC, News and Observer includes statements from his friends at the time of his death.[45] The article describes Peter in the last years of his life, as a “gaunt man in yard-sale clothing and flip-flops [who] would stop and talk for ages about his social cause of the moment.” He would push a shopping cart around the neighborhood. “If he met someone new, he would reach into the cart to pull out a voter registration form to sign the person up on the spot.” One friend reflected on Peter’s socialist education and remarked that it “really established a pattern. … Peter spent his entire life committed to helping other people and finding ways to build what he considered a more just, better world.” A local neighborhood organizer states that, “Peter doesn’t stand out as a leader, but he was somebody who was consistently available to do the many small things that needed to be done. And therefore, things happened. Phone calls were made, and letters to the editor were written.” The article mentions that suffering from prostate cancer, in the end, Peter took his own life.

What can we learn from this brief look into the life of Peter Nemenyi? To the scholarship of Black Mountain College, Peter’s story adds yet another perspective to the collection of research and stories about the college. For example, there were many faculty members at BMC who were refugees of the war. Peter’s story, as a student refugee, broadens our understanding of the history of refugees at BMC. Peter’s work with minorities in statistics and with civil rights groups sheds new light on the legacy of BMC and integration in higher education. Peter’s success as a mathematician—receiving a PhD from Princeton and having his name on an important statistical test, for example— shows that there are alumni of BMC who have achieved greatness in professions outside of the arts. Peter’s story makes it clear that the significance of BMC is not restricted to the arts but has more far-reaching implications.

While Peter’s story is unique and he stands out from the other Black Mountain College students, it is interesting to note that there are similarities to other students from the college. For example, compare Peter’s life to that of Ruth Asawa’s. Ruth was another of the small number of students to complete all the requirements and graduate from BMC. She became a famous artist in San Francisco. Both Peter and Ruth were child refugees of the war, Peter coming to BMC from Europe and Ruth coming from the Japanese internment camps inside the US. Both had been helped by the Quakers in their time of need. Both attended BMC in the late 1940’s, overlapping for two years. Ruth took two mathematics classes and three philosophy classes from Professor Dehn, Peter’s advisor. And Peter took art classes from Joseph Albers, Ruth’s advisor. Each went on to careers in the areas that they had studied at BMC. Each came out of BMC with a sense of devotion to their community. It is striking that both individuals had a deep commitment to education and made this a centerpiece of their lives. In literature and exhibitions about BMC, it is heartening to see that Ruth Asawa’s story has rightly been celebrated and her artwork recognized. It is, however, disappointing that Peter’s contributions in academics and social change have so far been overlooked.

There is one last point that should be made before closing. The foundations of the education system at Black Mountain College were centered on democracy. At its heart, BMC aimed to educate students who would go on to be creative and productive members of a democratic society. The academic program, the living arrangements, and the work requirements, all helped to develop collaboration and respect for every individual in the community. Everyone was encouraged to be an active member of the community and to step up and play their part when needed. In many ways, a successful graduate of BMC was an alumnus who went on to promote and support a just and democratic society. In this respect, Peter represents one of BMC’s greatest accomplishments. Peter spent his life fighting for democracy and a just society. Peter’s life story provides another example of the possibilities that can come from an education, like that at BMC, dedicated to nurturing a respect for community and democracy in its students. Maybe the real story of Peter Nemenyi goes far beyond BMC, Mathematics, and civil rights. Peter’s story is one of resilience. He demonstrates the best aspects of the human spirit in a constant pursuit of justice. He exemplifies one of BMC’s most highly held ideals. Peter Nemenyi was an individual who dedicated his life to building a just and equitable society.

[1] David Peifer, “The Sciences at Black Mountain College,” The Journal of Black Mountain College Studies 12 (2021), accessed online.

[2] David Peifer, “Max Dehn: An Artist among Mathematicians and a Mathematician among Artists,” The Journal of Black Mountain College Studies 1 (2010) accessed online.

[3] Black Mountain College Records, Series II: General Files. 1933-1956. Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[4] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979), Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI.

[5] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels, Oral History with Peter Nemenyi, April 12, 2000, transcribed by Clea Benson, Columbia University Libraries, Columbia Center for Oral History, New York, NY.

[6] Peter Nicholas and Clea Benson, “Files reveal how FBI hounded chess king. Letters obtained by The Inquirer also shed light on identity of Bobby Fischer’s father,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 21, 2008 (Sun, Nov. 17, 2002)

[7] Black Mountain College Records, Series II: General Files. 1933-1956. Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[8] Willi H. Hager, “Paul Felix Neményi: Engineer of Encyclopedic Mind,” Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, ASCE, June 2009: 439-446.

[9] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[10] Willi H. Hager, “Paul Felix Neményi: Engineer of Encyclopedic Mind.”

[11] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[12] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[13] Willi H. Hager, “Paul Felix Neményi: Engineer of Encyclopedic Mind.”

[14] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[15] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[16] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[17] Black Mountain College Records, Series II: General Files. 1933-1956. Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[18] Mary Emma Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain College, (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2002), 113.

[19] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[20] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[21] Peter Nicholas and Clea Benson, “Files reveal how FBI hounded chess king.”

[22] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[23] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[24] David Hilbert and Stefan Cohn-Vossen, Geometry and the Imagination (2nd ed.), trans. P. Nemenyi (Providence, R.I.: AMS Chelsea Publishing, 1999).

[25] Ruth Asawa Papers (M1585), Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, CA.

[26] Tim Penttila, MAA review – Geometry and the Imagination, 2013.

[27] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[28] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[29] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[30] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[31] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[32] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[33] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[34] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[35] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[36] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[37] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[38] Peter Nemenyi, Sylvia K. Dixon, Nathaniel B. White Jr., and Margaret L. Hedstrom, Statistics From Scratch, (San Francisco, Holden-Day Inc., 1977).

[39] Peter Nemenyi, Statistics From Scratch, 14.

[40] Peter Nemenyi, Statistics From Scratch, 19.

[41] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[42] Peter Nemenyi Papers, (1952-1979).

[43] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[44] Peter Nemenyi, interview by Sheila Michaels.

[45] Vicki Cheng, “Requiem for a Social Conscience,” News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), June 29, 2002.

David Peifer has been a professor of mathematics at UNC Asheville for 30 years. His mathematical research — on low dimensional topology — is directly related to work begun by Max Dehn, who taught at Black Mountain College. Recently David’s research has addressed questions concerning the role of the sciences at Black Mountain College. For more than a decade, David has been a board member of the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center. Besides research, he enjoys spending time with friends, mountain biking, playing music, and roaming the local mountains searching for wildflowers.

Cite this article

Peifer, David. “In Search of Peter Nemenyi – a Black Mountain College Science Student.” Journal of Black Mountain College Studies 15 (2024). https://www.blackmountaincollege.org/journal/volume-15/peifer.